After weeks working on the boat on the hard the sail from Dunedin to Oamaru was a delight. It was great to be sailing again, and, miracle of miracles, both the hydrovane and head seemed to work — most un-boat like. On this trip we stayed in about 100m of water so had no trouble with cray pots, and spent our time playing with the sails and wind steering. Eventually, the wind died away, so about an hour out of Oamaru we turned on the engine and motored the last leg before picking up a mooring in Oamaru Harbour, kindly arranged for us by Kevin. There was a strong temptation to get the dinghy off the deck so that we could go for pizza and beer in town, but as we wanted to leave early in the morning the hassle of lifting it off and on managed to outweigh my greed (we had beer onboard).

We left early the next day trying to take advantage of a small weather window that would allow us to get to Lyttleton, though light winds were predicted. A fat kahawai caught en-route helped enliven the trip as the meteorology boffins were bang on.

We sailed and motored and motor sailed across the Canterbury Bight arriving in Lyttleton about 28 hours after leaving Oamaru at lunchtime on Friday. Picking up the mooring in Diamond Harbour we sat and watched a Maltese super yacht called Farfalla out in the harbour. They obviously had trouble with their hydraulic vang (a strut that pulls the boom down or holds it up) as it was removed and being fiddled with. Even the super rich are afflicted with the need for constant maintenance of their boats — though their hands probably don’t get very dirty.

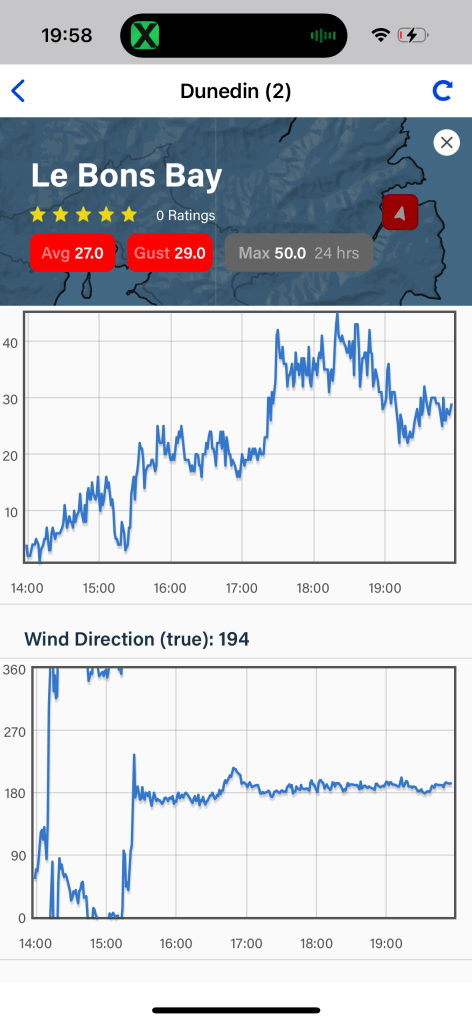

Timing our next leg was a bit tricky. A 24 hour southerly gale was forecast with ‘very rough’ seas and wind speeds of 30 knots. This is a little more than most prudent sailors would choose to go out in, but there was nothing but northerlies for the rest of the week and this weather promised a fast trip to Wellington. It is also the kind of weather we might easily encounter when offshore so it seemed a bit woosyish to run scared of it. Nevertheless, we felt some trepidation as we set off, watching the clouds gather in the south and pursuing us north. We were perhaps a little complacent, thinking that we had everything ready, but when the southerly finally hit it came with a punch stronger than expected. The wind veered 180 degrees and the windspeed increased from 25 to 45 knots in what felt like an instant. Note that when wind speed doubles the energy quadruples, so we went from a pleasant sail in good winds to being smashed in a maelstrom, way overpowered, and having to reef in strong winds. Chaos reigned for a few minutes as we sorted ourselves out.

The wind speed given in weather predictions is the average expected, so one can expect gusts up to 40% stronger. Unfortunately, we found that the average wind speed was higher than predicted, with the average being in the high thirties and low forties, and with a maximum measured by our instruments of 48 knots. The relative shallowness of the sea along the coast created steep, often breaking waves that were close together and which seemed to come from two directions. The first would hit us diagonally just aft of the beam and slew us round so that we were beam onto the larger wave pattern which came from directly behind and would subsequently try to lay us over. Lying beam onto breaking waves is particularly dangerous as scientific tests have shown a reasonable chance of being rolled if wave height exceeds one third of the boat’s length. The waves were predicted to be 3m but seemed much higher than that to us, but we passed unscathed and the hydrovane did sterling service through the night when we couldn’t even try to turn the boat to avoid the waves in the pitch dark. At about 3am we took the main sail down completely and continued under storm jib alone as the wind was coming from directly behind us veering slightly from our port to starboard side and threatening a crash gybe. The reduced sail area helped to depower the boat, which continued on at about 7-8 knots, a good speed for our boat, under storm jib alone. Normally we would steer off when in this position (so the wind isn’t directly behind), but we didn’t want to close with the land on our left, or head way out to sea on our right. Nor did periodically jibing from one side to the other seem like a great idea as we need to use running back stays when flying our storm jib to help support the mast. These make jibing that much harder (the stays prevent the boom from rotating from one side to the other) as they have to be connected and tensioned at the stern, and coiled and returned to the shrouds when disconnected, a bit of a hassle and safety issue in the dark in poor conditions.

We had hoped to continue to Wellington but had planned a possible stop at Cape Campbell on the north east of the South Island if we needed to wait for the correct tide or if Cook Strait was too rough. Both turned out to be the case so we edged to port in between waves to try and get into the shelter of the Cape. This turned out to be far from easy, as the wind and waves wanted to push us past and we had to turn and punch into 30 knot winds. It took about an hour to get into shelter with sheet after sheet of solid water being flung over the deck as the waves smashed against the bow. On the positive side we were able to watch dolphins leaping out of the waves and surfing down their faces.

The anchorage at Cape Campbell was only about 3m deep but still quite exposed. Cara and I spoke briefly about carrying on to Wellington or Port Underwood but in the end decided enough was enough and it was time for a breather. As it happened the weather, which had been slowly improving, blew itself out not long after and we were able to enjoy an early tea and a good night’s sleep.

Cape Campbell

The following day the sea was like a millpond, a radical change from the conditions we had endured for some thirty odd hours just the day before. We left early to time our arrival at Wellington with the ingoing tide and enjoyed 15-20 knot winds, perfect for Taurus, and the sight of half a dozen Albatrosses skimming millimetres above the waves.

The notorious Cook Strait provided fantastic sailing, and the cherry on top was a pod of dolphins, much larger to those we are used to at home, who joined us for the approach into Wellington.

Our entry into Wellington Harbour went smoothly, though the numerous warnings about rip tides and rocks ensured we kept a good look out, and we headed into Evans Bay marina, where we were glad to see Max, Cara’s brother’s father in law, waiting to help us dock.

The experience of sailing in the gale up the east coast was certainly valuable, and something we wanted to have under our belts before going off shore. Taurus certainly proved herself capable, but the soft mushy crew inside were quite challenged and are not overly eager to repeat the experience, especially in a coastal area due to all the extra issues this creates. The tactics we adopted worked OK, but in hindsight dropping the main meant that we couldn’t heave to (a safety measure that sees the jib and main placed in opposition, effectively stopping the boat) but in the circumstances of wind strength and direction it was probably the right call. Apart from that decision everything else went well and I would expect/hope to have greater distance between waves offshore which would have made life much easier. We also need to consider what drogue or sea anchor to purchase before leaving for Tonga. I had intended to buy or make a Series Drogue, but these weigh about 60kgs, and I really don’t know how we would have gone trying to launch something like that in the conditions we had — let alone in conditions potentially much worse. As seems standard with sailing, experience provides nuance rather than answers, greater awareness of issues that have to be weighed and considered.

Leave a reply to craigdec70f4f95 Cancel reply