As we left Sir John Falls to return up the Gordon River, the rain fell and the temperature seemed to plummet. We had grown used to bright sunshine and still conditions, so this grey, damp, and cold new world muted our enjoyment of the scenery somewhat. We were also apprehensive about our batteries’ charge state (with the alternator still providing a weak charge) and the likelihood of meeting the big commercial ferry around some bend of the river.

Happily, we avoided the ferry, and the big wave we received from its crowd of passengers, braving the rain on the exposed deck, made us forget the rain for a while. Eventually, we escaped the river and could raise the sails to enjoy a fast trip back to Strahan. Alas, when we turned the engine back on to anchor we found that the alternator had given up the ghost completely, and was providing no charge at all.

The isolation of Strahan was brought home to us again as we tried to find a replacement alternator for our old(ish), British engine. The search was further hampered by our need for an ‘above ground’ unit — one that doesn’t ground to the engine and cause potentially harmful stray current. To cut a long story short, we eventually found an auto-electrician in Launceston with the knowledge and willingness to help, and we had two units freighted out to us. Why two you may ask? Well, a wise boatey saying has it that “one is none, and two is one,” a maxim that emphasises the importance of having redundancy aboard.

To compound matters, the incredible weather we had experienced for our first week in Strahan soon became a distant memory. The rain fell in sheets, and every night seemed to provide a fresh gale from one quarter or another. Power rationing doesn’t come easy during long, cold, wet days. In the end we got in touch with the local council and arranged a berth on the town jetty so that we could plug into the mains, and walk on and off the boat. The only downside was that the northerly gales blew us against the jetty and the wide piles, designed for large fishing boats, required some creative fender work. Nevertheless, life was much easier that it had been on anchor, and the chap in charge of the jetty kindly decided not to charge us for our short stay.

We used the time whilst waiting for the alternator to arrive (and subsequently, for a weather window) to check out the local tourist trail. One night we attended the play (perhaps pantomime is more accurate) The Ship That Never Was. This fun drama is Australia’s longest running play (at thirty odd years) and recounts the last great convict escape from Sarah Island. Wrap up warm and try not to sit in the front row if you don’t want to participate!

Another day we took the old mining railway along the King River with William from Sea Eagle. It was nice to get a different view of the area, and to again marvel at the hardiness of the pioneers who tried to tame this rough terrain.

An expedition to Queenstown kept us out of mischief another day. We took the school bus to the local ‘big smoke’ to see what we could find. The alien landscape surrounding the town, created by decades of mining, provided mute testament to the power people can wield over nature, whilst the shabbiness of the town itself, now the mine is shut, speaks volumes about the vicissitudes of human endeavour. The ruined land remains, but most of the people and the wealth are long gone.

The wisdom of our trip was looking a bit dicey when we had ‘finished’ the town by 10 am, with the return bus not leaving till mid-afternoon, but then we found the local museum. Its eclectic collection is so large that we ended up spending several hours there and still missed a good portion of it. Cara even found an old operating theatre and anaesthetic equipment to play with!

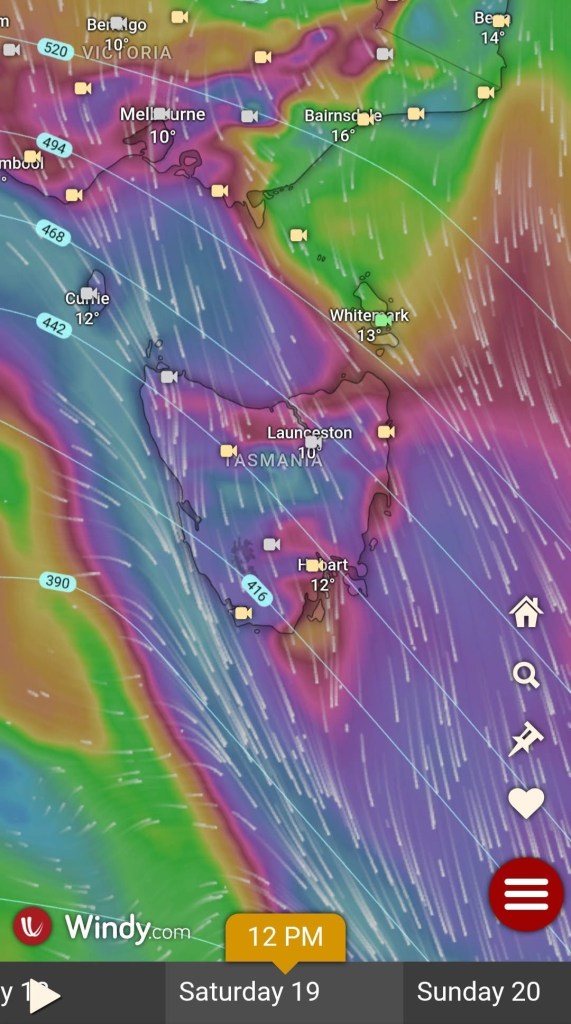

With the new alternator installed we began looking for a weather window in earnest. However, even the weather guy on ‘Weather Watch’ (a useful internet resource) was surprised by the never ending sequence of storms rolling across South Australia and Tasmania. Rather than risk a nasty Southern Ocean experience we were happy to wait.

Out of the blue one afternoon we received a call from Michael from Sea Eagle. A little cryptically he asked if we had dive gear on board and if one of us could dive. It turned out that the lads had run over a mooring line at Birches Narrows, which had become wrapped around their propellors. Michael had been diving on the boat all morning with a 2mm wetsuit and a dolphin torch, but hadn’t been able to free the boat. Sooner or later anyone who goes boating ends up in this predicament, and we have certainly been in the club ourselves once or twice. We had the gear and were happy to help, so Michael, wanting to get free as soon as possible, hired Sophia, one of the local tour operators, to bring us to them first thing in the morning.

It was exhilarating to race down the Macquarie at 30 knots, a rather different experience to Taurus’ more stately 5 knot average. However, our mission of mercy almost became mission absurdity when my dive regulators began free flowing a couple of minutes after I entered the water. This can be caused by cold water freezing small parts in the regulator, as well as by fresh water such as is found near the river’s mouth. A further factor might be plain lack of use. I last dived in Noumea and the gear was overdue for a service. Anyway, as I was all dressed up with diving thermals and an 8mm wet suit on I felt duty bound to do what I could.

I have to say that I really dislike free diving under boats. Having smoked for many years my lungs aren’t great, and having almost drowned in a kayaking accident I have a residual fear that doesn’t help me conserve what little air my lungs can hold. I can never quite shake the idea of getting caught on something and being unable to surface. The 10 degrees water, pitch dark only a metre or so beneath the surface due to the tannins from the peaty soil, did little to help me relax. The cold seemed to prevent me catching my breath, and all I could manage was lots of short dives.

Even with a decent dive torch I literally swam into the propellors before I saw them. The lack of visibility meant that I used a good deal of air just finding the props each time I dived, and then had to desperately surface before I could really achieve anything. Eventually, I freed one propellor and moved on to the next. The rope was tightly wrapped on the second shaft, but I was able to loosen enough rope to tie it to a fender so I could use it to guide myself back to the propellor, and avoid wasting time and air. After what seemed a long time the rope was finally cut away. I couldn’t help but admire Michael who had been trying to do this with a thin summer wet suit and a crappy old torch. Bugger that!

Eventually the propellors were clear and I had another quick dive to check that the rudders were clear — another bump on the head as I swam into them blind. Michael suggested I check the stabilisers too, but after a couple of dives in which I couldn’t even find the stabilisers I felt that enough was enough. The exercise had been way out of my comfort zone. Of course, being challenged isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and no doubt the experience will be helpful when we next ‘catch’ a rope ourselves. The upshot was a cruise with William, Michael, and Steffani, Michael’s wife, back down the Gordon River before being treated to dinner at the Strahan pub.

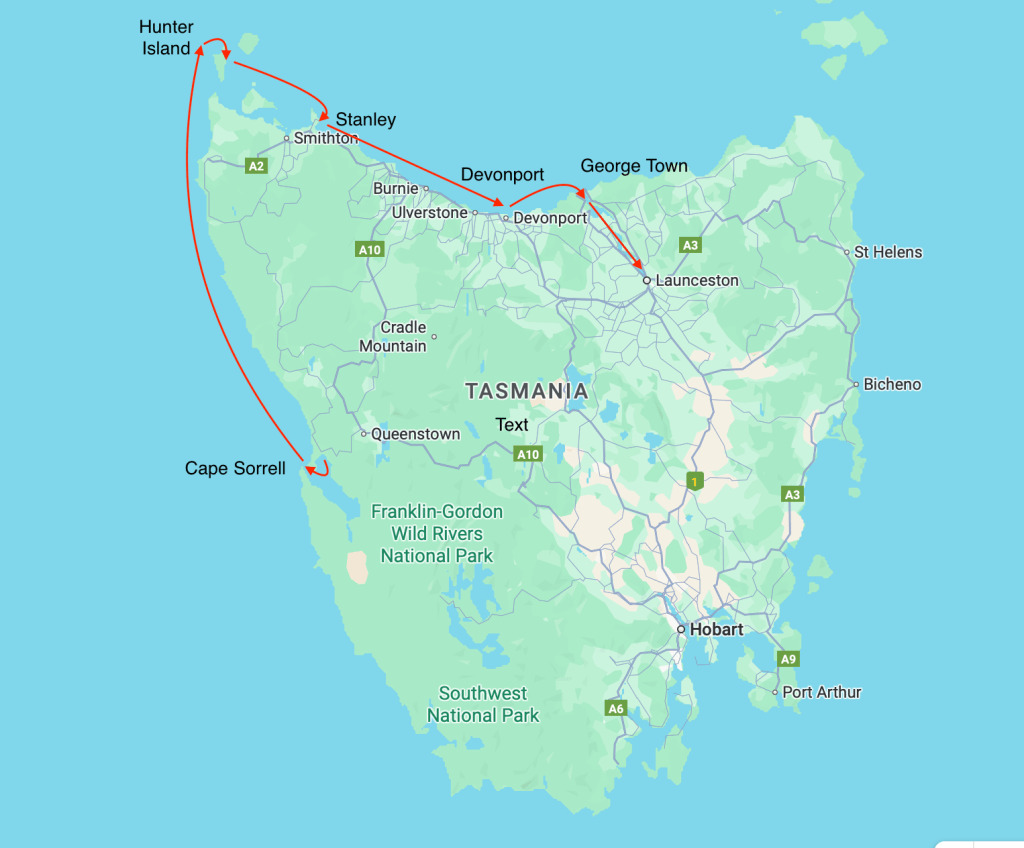

Our wait for a decent weather window finally seemed to bear fruit, and a predicted 20-25 knot sou-westerly looked like just the ticket for our 24 hour sail to Hunter Island on the North West corner of Tasmania’s coast. We left Strahan a day early to take advantage of the outgoing tide through Hell’s Gates, and anchored in Pilot Bay. In the afternoon we took the dinghy ashore for the short walk to the Cape Sorrel lighthouse.

We didn’t leave till midday the following day, a Monday, so as to arrive at Hunter Island with the strong tides in our favour. Once clear of shelter the wind and swell increased dramatically, and we were soon flying along with 25 knots on the beam in a swell of 1-2 metres. The wind and swell in these waters can travel thousands of miles before it reaches Tasmania. It’s only obstruction, possibly South America or Antartica. As a young man I printed maps for the army. I recall a course I attended in which the instructor tried to make us understand that the wetness of water can vary. In my ignorance I scoffed at such silliness, but he was of course correct. Our trip up the West Coast made me wonder if the strength of wind can also be tied to more than its mere speed. Can air be more or less dense, a swell be more powerful than its mere size suggests? I don’t know, but as conditions worsened the power of wind and wave seemed way beyond that suggested by the instruments.

As anyone who films the sea will tell you, video flattens the sea, so it doesn’t really provide a true idea of the actual experience. The clip above was taken just after we had left Hell’s Gates. You can see in the footage of the chart plotter that the wind is about 25 knots. In the subsequent video the wind has only risen a couple of knots, 27 is indicated, but there is clearly a good deal more power in the breeze. Taurus is no longer rolling, but is heeled to leeward and we are racing along at 7.5 knots according to the instruments.

The wind and swell continued to increase, and we shortly afterwards furled the jib and raised the storm jib, the orange sail that you can see in the videos stowed in readiness on the dinghy. We hadn’t expected to need it in the 20-25 knots predicted, and the main reason we had it set up was because we hadn’t used it for a while. It was a good job it was ready to go. Decreasing the sail area and bringing the centre of effort closer to the mast allows the boat to better cope with strong winds. And strong they got. Before long the wind was sitting on 35 knots with sustained gusts of forty. If all the predictions hadn’t clearly stated that the wind was going to drop it would probably have been prudent to have turned around. The Beaufort scale offers a useful guide for context: 22-27 knots is classed as Force 6 and entitled a ‘strong breeze;’ 28-33 knots, Force 7, and called a ‘moderate gale;’ 34-40 knots, Force 8, and a ‘fresh gale;’ and 41-47 knots, Force 9, and a ‘strong gale.’ The scale tops out at Force 12 with 66 knot winds and over, classified as Hurricane force. Promised a strong breeze we found ourselves verging on strong gale conditions — and the weather was rapidly deteriorating. You can see why we were concerned.

Happily, sustained gusts of nearly forty knots was as bad as it got. However, the sea state had altered with the elevated wind, and as we were heading north and the swell is predominantly from the west we were beam on to the powerful waves. The strong winds from the sou’ west also created a seperate and decent sized wave train that rose from a different direction from the swell, making for confused seas and short gaps between peaks and impacts. We conservatively estimated the swell at 5-6 metres, which is far from unusual in this area. The current wave record holder for Cape Sorrel was a monster that measured 19.83 metres, in winds of 83 knots (154 km/h), in 1982. Yikes!

Memories of sailing in difficult conditions seem to consist of snatches of images. I recall Taurus being thrown so far over to starboard that the sea threatened to flow over the cockpit coaming, and then another large wave smashed into the port beam, crashed across the dodger windows and seemingly half way up the mast. The sailing conditions were not ideal. Still, when we weren’t being chucked about by the waves we were sailing well, so we decided to maintain our sail plan of storm jib and three reefs in the main. This kept us powered up and moving quickly in the rough sea state. We kept a close eye on the waves to make sure they didn’t start to break, which makes the risk of capsize far higher, and would have forced us to adopt more rigorous storm tactics.

The wind was supposed to drop by midnight, but ultimately it kept us on our toes until about 3am. It was a memorable night and probably one of our worst weather experiences. The big positive was that Taurus swam through the conditions without ruffling a feather — to mix my metaphors, or perhaps she has penguin DNA. We did manage to break a couple of things, such as a solar panel that we should have strapped down. You can imagine what happens when a boat the size of Taurus is thrown onto her beam and tries to sit on a flimsy piece of glass and aluminium — nothing good. In similar fashion our canvas dodger on the port side had its grommets ripped out — the material unable to withstand the resistance of the water as it was pressed against it.

There are several downsides to owning a full keel, heavy displacement, steel boat, but when the pooh hits the fan the inherent strength and seaworthiness of the design more than makes up for them. We have been asked in the past if such experiences put us off sailing. Well, they aren’t pleasant, but they strike at the heart of why we chose to go cruising on a small boat. Robert Pursig, author of Zen and the Art of Mortorcycle Maintenance, and a sailor, explained it better than I can. He said,

Those who see sailing as an escape from reality have got their understanding of both sailing and reality completely backwards. Sailing is not an escape but a return to and a confrontation of a reality from which modern civilization is itself an escape. For centuries, man suffered from the reality of an earth that was too dark or too hot or too cold for his comfort, and to escape this he invented complex systems of lighting, heating and air conditioning. Sailing rejects these and returns to the old realities of dark and heat and cold (‘Cruising Blues and Their Cure,’ originally published in Esquire, May 1977).

The world also used to be frightening and dangerous (and of course remains so for those born in unlucky places). The opportunity to be scared and experience the elemental nature of our world is also therefore something of a privilege. It is far too easy for life to slip away in a blur of work, tv, shopping, and so on. That at least was my experience. One year blurs into another, and another, and another, with little to tell them apart. In the year that we have been sailing we have had so many experiences, high and low, that the difference between our old comfortable existence and our current life is chalk and cheese.

Cara needed to be in Launceston for the Monday coming to start her short term contract. We therefore had to concoct an itinerary that allowed us to avoid the now regular sou’ easterly winds. Having arrived at Hunter Island earlier than expected (we had been sailing at 9.5 knots thanks to the strong winds, almost double our standard 5 knots) we dropped anchor and went straight to bed. We were up at 5am to beat the predicted easterlies and arrived at Stanley mid-morning, we left at 11pm that night to arrive at Davenport at dawn. We spent that night at the Mersey Yacht Club and left the next day for the six hour trip to George Town. The following day we headed down the Tamar River, a full seven hour trip that we ultimately completed in the pitch dark — having had to wait for the strong tide to turn.

As you can imagine, we were pretty tired by the time we got to Launceston at 8pm on Saturday night, and our fatigue perhaps helps to explain our hitting a pedestrian footbridge trying to get into the marina. But it’s past time to wrap up, so that tale will have to wait for the next instalment!

Leave a comment