In the previous episode we were on anchor in Recherche Bay, supposedly relaxing before heading out to sea at midnight for the trip to Port Davey. Then the bilge alarm went off. A quick inspection revealed a startling amount of water in the bilge — perhaps 2-300 litres. Taurus‘ bilge can be measured in feet, so she can swallow an awful lot of water before it makes its presence known.

We quickly worked out that the water was coming in via the stern gland. As I mentioned previously, this is a specialised piece of equipment that allows the propellor shaft to exit the boat and spin without allowing water to come in. Our particular brand of dripless stern gland, Sure Seal, has provision for a spare seal to sit on the propellor shaft ready to be deployed if the one in use fails. However, I had never undertaken this job, and would have preferred to learn with the boat well out of the water. Removing the old seal in situ seemed likely to make a bad situation worse, and if there were any problems with the new installation we could end up with a big leak, possibly exacerbated by using the engine. Being in a fairly remote part of Tasmania I was not super excited at the prospect of ‘giving it a go.’

Still, ‘fortune favours the bold,’ or perhaps ‘fools rush in where angels fear to tread’ is more apt. We decided we had little choice but to try and change the seal. In such circumstances having a Starlink unit on board is a God’s send. Whatever you might think of Mr Musk, it’s nice to be able to watch a YouTube video detailing the process rather than wading in blind.

Access was naturally an issue. But by lying on the engine I could just about reach the stern gland. I was once agin very thankful that I had cut out a section of the bulkhead that sits above the gearbox so that I can gain access to the drive unit. Trying to do this job from the rear access way — which demands balancing on one foot with the other tucked round your ear — would have been a nightmare, and probably decided me against attempting the job in the water.

Much to my surprise, the job turned out to be relatively painless. Water didn’t pour in, and within ten minutes we were done. I wouldn’t hesitate to change the seal in the water next time, though now of course we don’t have a spare seal on the prop shaft. Next time the shaft will have to be taken apart to get a new seal on. That’s definitely a boat out of the water job.

Our big OMG bilge pump (the ‘Oh my God’ pump, for when things get bad) quickly emptied the bilge and we ran the engine to check everything was working OK.

Here we discovered the next problem. I had been wondering why the seal had failed, and it turned out that the pillow block, that secures the prop shaft, had somehow worked loose. This allowed the shaft to slam forwards and backwards a centimetre or so as the boat was put into forward or reverse. This is the kind of abuse that seals don’t take kindly to!

Why should this come loose, and why should it be bolted through a slot rather than a nice tight hole? Well, having replaced the gear box a while ago I may have loosened the bolts and not tightened them up again sufficiently — I don’t remember loosening them but possibly I did. Alternatively, they may have simply worked loose over the past five years or so since they were last looked at and the bearing inside the block replaced. Either way, there was no shaft movement after the gearbox work was done, as we checked everything at the time. Why the slot that allows movement? Presumably, I guess, for fine tuning shaft alignment? The fix was simple. We put the block back in place and I tightened up the bolts as much as I could whilst holding two spanners at arms reach. My plan is to put a rattle gun on them when I get a chance, maybe with new bolts and spring washers, to make sure that they don’t come loose again.

So, with the sea back where it should be, on the outside, and the boat operational again, it was time to resume relaxing. At midnight we hauled the anchor and headed out to the Southern Ocean.

The sail was fairly smooth, with a nice beam wind and gentle swell. A few hours later we had the excitement of threading our way through the islands that sit to the south of Tasmania in the dark. Thankfully, Australian charts are pretty accurate (though locals tell you of numerous errors), so trusting our chart plotter meant that the exercise was straight forward, if a little anxiety inducing. Seeing the vague silhouette of large rocks emerging from the darkness, almost close enough to touch (so it felt) was an experience that focuses the mind.

Other potential obstacles were fishing boats. We could identify them by their bright white lights, which drown out any navigation lights they might display, and of course their masters had chosen to turn off their AIS devices so they didn’t appear on our chart plotter. Thankfully they were close inshore so we were able to keep our distance.

We soon arrived at the South West Cape, arriving more or less bang on time at 9:00 am. However, the predicted shift in wind failed to materialise and the northerly wind kept on blowing, but now it was blowing from the direction we wanted to go in. We experimented to see if we could tack across the wind to make progress, but with the added hindrance of the swell we were making very little ground and decided to turn to the engine, hoping that the westerly wind would soon appear. Bashing into the wind was slow going, we were down to around two and a half knots for a while, but the wind eventually eased and we were able to thump along at four or five knots.

The grandeur of the Tasmanian seascape is awe inspiring. Before it was realised that Tasmania is an island, all the ships destined for Botany Bay or the Pacific would round this coast. With poor charts, unwieldy ships, and often sick crews, it’s no wonder that so many foundered on this wild and unforgiving coast. I happily spent hours watching albatross fly against a background of spume dozens of feet high, thrown up from the sea crashing against the cliffs. If we had been able to sail I would have been a pig in poo.

The wind finally veered to the south west just as we were arriving in Port Davey. It was perhaps a good thing that it came in late because it arrived with a hiss and a roar. We were relieved not to have been caught on that rugged lee shore in the gusts that quickly started to blow up.

Port Davey is about as isolated and wild as isolated and wild gets in first world nations. No roads lead here, and the marine reserve, national park, and world heritage area can only be accessed by boat, an 85 kilometre hike, or by an hour’s flight in a small plane. There are no permanent residents. The area encompassed is substantial, about three times the size of Sydney Harbour. Incredibly, it being winter, it seemed that we had the place to ourselves.

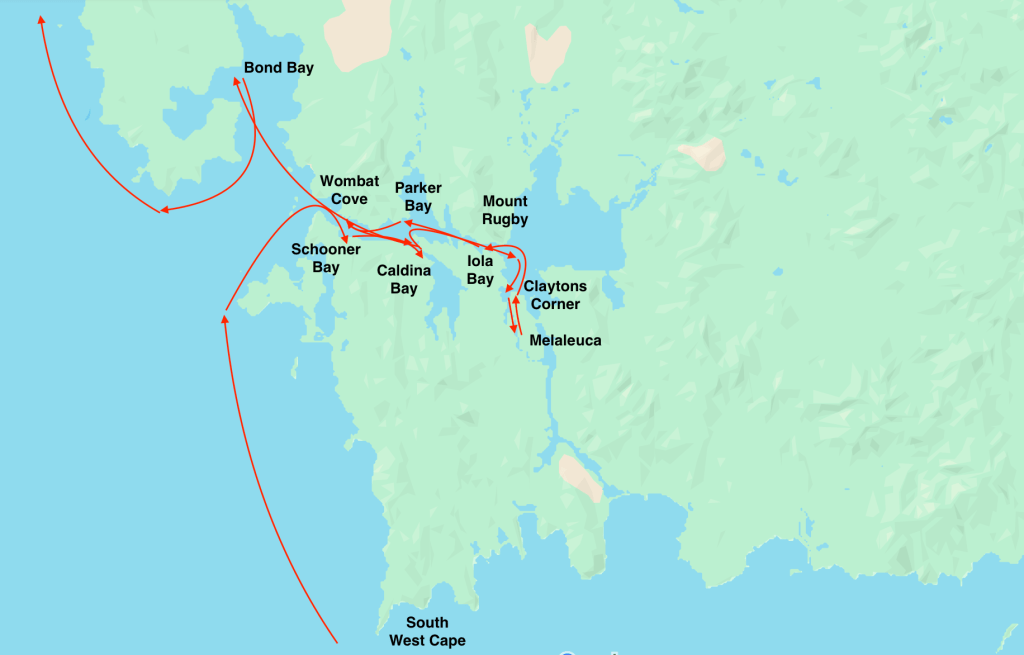

Once inside the protection of the surrounding hills we found a far more pleasant day. We entered Schooner Bay and dropped the anchor to enjoy the peace and quiet. Unfortunately, as the sou’ westerly winds increased outside, gusts of wind, known variously as willywaws, bullets, or katabatic winds, flew down the slope of the bay, accelerated by gravity, and sometimes heeled Taurus over. In these conditions a good night’s sleep depends on the degree of faith you have in your ground tackle. Fortunately, we know our system well, and have never dragged once the anchor has been set (touching wood as I write this). In our fatigue we slept like babies.

We woke next morning to find a white bellied sea eagle had joined us for breakfast. After the hustle and bustle of Hobart, and the work and worry of the voyage, it felt like a weight had been taken off our shoulders as we took in the peace and silence.

We moved mid-morning to get away from the ongoing gusts, and headed to Casilda Cove. This beautifully protected little bay has steel tie back points so that boats can use stern lines to pull themselves back into the bay. From here we took the dinghy across the channel and walked up Balmoral Hill to check out the views.

Note the dark brown colour of the water in the photo above. This darkening, caused by tannins leaching out of the peat soil, creates a rare marine environment. The tannin-rich fresh water overlies the tidal saltwater and restricts sunlight from penetrating further than the top few metres. This limits the normal growth of marine plants, allowing plants and marine invertebrates that normally grow in much deeper waters to thrive. The unusual marine life is one of the reasons why the area was granted world heritage status.

Later in the day we shifted to another bay called Clayton’s Corner. For many years a couple, Win and Clyde Clayton, lived and worked here, creating a home out of the wilderness. Their house is now preserved by a volunteer group, and is open for visitors to use as they will. If we could have worked out how to use the wet back we could have taken a bath.

From here we took the dinghy down a shallow inlet to Melaleuca. A small airstrip there provides access to the national park, a couple of huts provide shelter to trampers on the South Coast Track, and scientists studying the region have accomodation from which they can fly in and out. We actually found three scientists in residence when we visited. They had been fishing for sharks which can apparently provide evidence of the presence of heavy metals in the water. We were all a little surprised to meet, as we all thought that we had the place to ourselves, but they were flying out the following day so we didn’t grumble about their intrusion.

Also at Melaleuca is a little museum devoted to Deny King. A local legend who lived here from 1945 until his death in 1991. Deny was a miner, naturalist, painter, and environmentalist whose work encouraged the creation of the Port Davey National Park and World Heritage Area. Quite a guy.

Recognising that we had another day of good weather in hand we were determined to climb Mount Rugby. This 750 metre high peak dominates the local landscape and promised incredible views. We had to move the boat to another anchorage to access the track. We chose Iola Bay, a fabulous little place entered through a narrow inlet from the Bathurst Narrows.

We had read that the climb up Mount Rugby takes about five hours return, but we wanted to start early because it gets dark at 4:00 pm and neither of us wanted to be blundering around in the bush unable to see. The ‘track’ is maintained by the local wallabies, and often reflects their height and shape, so forming small tunnels for the average human to have to push through. Due to the peaty soil it was also very wet and slippery. The last hundred meters to the peak is a jumble of large boulders and scraggy bush. Walkers are advised to mark their route when ascending so they can find their way back down. Unfortunately, this has resulted in a number of bits and pieces of marked track that converge and diverge, and one has to be careful not to end up getting lost or going the wrong way .

As I boulder hopped the last stretch an experience I had a couple of years ago played in the back of my mind. I had been walking the Tin Range in Port Pegasus in Stewart Island, a remote area in New Zealand similar in many ways to Port Davey. I was trying to find the summit of the ridge, and was bush bashing through scrub high over my head. Finding a rock outcrop I decided to climb it to orientate myself. From the top I could see the ridge stretching away so began to climb back down. In the process, the boulder I was hanging off, shifted and began to fall. I threw myself away from it and landed in a bush with the boulder smashing into the ground about a foot away. It still gives me a cold sweat to think about what would have happened if any part of me had been underneath that rock when it landed. Cara had headed back down the ridge, and any search party would have been hard pressed to find me.

With this in mind, and Cara having decided to stop at the ridge, I was wary of taking any silly risks. Something as minor as a sprained ankle or hyperextended knee could be a major problem in this environment. Cara would have no chance of carrying me in the rugged terrain, and any help is a long way a way. Unfortunately, you could only proceed by taking a few sketchy risks: climbing large slippery boulders, jumping across gaps, and constantly slipping and sliding on the muddy path. It would be an easy place to get hurt, but the views from the top were worth it.

I was glad to get back to the dinghy and Cara. Full time cruising doesn’t keep you fit, so we were both pretty tired and looking forward to putting our feet up.

With the weather on the change we needed to move to somewhere that offered better protection from the north. On the way we stopped at Parker Bay. This somber spot is where the body of Critchley Parker was found in 1942. Parker had been surveying Port Davey as part of an initiative to create a Jewish homeland in Australia. He was dropped off by a local, intending to walk to Fitzgerald, but was forced to turn back due to foul weather. Unfortunately, his matches having gotten wet, he was unable to signal for help and died of hypothermia and starvation after some fifty days alone. His body, and diary, were found five months after his death, and he was buried nearby. Surrounded by scrubby bush his grave seems a miserable place to spend eternity, but I guess he’s not complainig.

As the wind started to rise we carried on up the channel to Wombat Bay. This anchorage is advertised as well protected from the north, and once again there were strong points to tie back to. However, with the extra high tide and dark coloured water we couldn’t find them, so we ended up tying back to some stout looking trees. The protection was passably good, but we still rocked about as strong gusts found their way into the bay. We considered staying for a later sou’ westerly change, but we had a lot of chain out, about fifty metres by the time we’d reversed back to shore. This meant that if anything were to happen to our stern lines in the southerly we could swing onto a lee shore in no time at all. The protection from the south west appeared adequate, but, as we had found out in Schooner Bay, it can be very difficult to judge without knowing the dynamics of a place. Sometimes the hills that you think will provide protection work instead to accelerate the wind into you.

Rather than take a risk and maybe have a couple of uncomfortable days we decided instead to hightail it back to Casidila Bay. The wind in the channel entrance was howling, with spin drift being thrown up from the wild white horses. Heading the opposite way we found that the entrance to Casidila was sheltered.. We anchored and stern tied back, pulling Taurus as close into the bay as possible. The rocks behind ended up a little close for comfort, but we had a metre and a half of water under us at low tide and we sat rock solid for the next 48 hours as the rain pelted down and the wind roared over our heads.

Between a break in squalls I grabbed some muddy clothes, besmirched from slipping and sliding on the Mount Rugby track, and threw them in a large bucket on deck. I added rain water from the dinghy and agitated away with a bare foot. To my surprise, within a few minutes the temperature of the water made it simply too painful to continue. I hadn’t realised just how cold it was; a salutary lesson not to fall in the water!

With the front having passed we moved to the northern arm of Port Davey and anchored in Bond Bay. From here we could take the dinghy up the Davey River about five miles, but as the weather turned again, creating the risk of breaking waves up river, we decided not to risk it. Instead we took a trip ashore to look for the remains of an early settler’s house.

Our last day in Port Davey was spent on the boat again, sheltering from rain and another northerly front. The wind was due to swing to the sou’west and slowly die the following day. This seemed an ideal weather window to get north. We could sail most of the 18-20 hours to Macquarie and pass the notorious entry, officially known as Macquarie Heads, but universally known as ‘Hells Gates’ — the name bestowed by convicts who passed through — in light winds. Due to the lack of shelter from westerly swells and wind, the narrow entrance, and the surrounding shoals and strong currents, cruising guides advise not to attempt the Gates in strong westerly conditions, or in the dark. The Tasmanian Anchorage Guide simply states that in “gale force NW conditions or when there is a heavy NW swell or W swell, there can be dangerous breaking seas anywhere E of Cape Sorrell [the headland to the west of Macquarie Heads]. In these conditions it is most unwise to be in this vicinity.” As the wind at this time of year on the West Coast seems to be a never ending series of Sou’ westerly gales and Nor’ westerly gales, opportunities to enter Macquarie can be few and far between.

We kept a close eye on a weather app that provides real time wind updates. By 6:30pm the wind had swung to the west and it was time to go. It was pitch dark, and I admit to being apprehensive about leaving Port Davey and the conditions we might find out at sea. The power of this place demands respect. Here the Southern Ocean, which has run unchecked for thousands of miles, meets land. The seas pile up as the ocean floor rises to form jagged rocks and cliffs. On the tail of a northerly gale the conditions were unlikely to be pleasant, and we were gong to have to force our way through until we could round the headland. Our modern navigation equipment was a God’s send as our position was constantly updated, but my mind kept returning to the thought of what we would need to do if the engine was to die, and we had to try and sail back between the rocks and islands to a safe anchorage. It wasn’t a comforting thought.

Fortunately, the Lister Petter kept thumping away, smashing Taurus through the waves and swell, and we finally rounded the corner and could retreat from the unequal fight against the elements. Naturally the wind veered sufficiently to prevent us sailing for another hour or so, but finally we were able to unfurl the jib and turn off the motor.

As expected, the waves stirred up by the strong northerly had become confused by the westerly change. These combined to create a violent movement onboard which prevented us from getting any sleep. Adding to the challenge, the wind kept heading anti-clockwise so that our predicted sou’ westerly ended up as almost a sou’ easterly. As the night wore on the wind ended up blowing from directly behind us. We routinely use preventers, which stop the boom smashing across the boat in a crash jibe, so the conditions were more irritating than dangerous: the jib kept collapsing and refilling, explosively yanking on the lines and gear. We needed to pole it out, but feeling tired and nauseous neither of us were keen to attempt the operation in the violent seas and darkness. Instead, I played with different amounts of sail, altered the sheets and cars, dropped the main, but in the end nothing really worked. Ultimately, the snapping of the sail gear grew so wearisome that I furled the jib and put the engine back on. I hate to motor when I can sail, but sometimes you just have to say the hell with it. Come daylight we poled the jib out and raised the main to the third reef, holding the boom amidships to try and reduce the roll. The ride still wasn’t comfortable, but we were moving and it was the best we could do.

Despite the conditions we made fairly good time, passing Macquarie Lighthouse at Cape Sorrell at 1pm. Our timing was near perfect as slack tide was due at 1:30pm, the calmest period to enter the harbour. We avoided the rocks that the lighthouse warned against, watching fascinated as the waves smashed themselves into atoms against them, and rounded the cape to head towards Hells Gates. The swell remained surprisingly powerful, and for a brief moment Taurus surfed along at 10 knots. The entrance to Hells Gates is guarded by a mole on the western side, a wall built in the convict era to reduce the swell, whilst to the east an impressive series of breaking waves give notice of the sandy shoals. In the light conditions we had no trouble motoring in, but it was all too obvious why this place is best avoided in the dark or strong westerlies.

Having passed the Gates we then needed to follow various channels through a maze of sand banks. How people managed to get in and out of this harbour in the age of sail, heaven only knows, but it is little wonder that so many ships were wrecked here.

Finally we reached Strahan, a picturesque little town, dropped the anchor, and unshipped the dinghy. We rowed across to the local pub and ordered some food and a beer. Ah, the glorious benefits of civilisation!

Then it was back home to a boat oddly still and quiet after all the frenetic movement we’d grown used to. It was time for a good night’s sleep.

Leave a comment