My father was fond of quoting Harry Day, a World War I, Royal Flying Corps ace, who apparently said, “Rules are for the guidance of wise men and the obedience of fools.” It was, therefore, perhaps their fault that Cara and I were playing fast and loose with the rules in Hobart. You are only supposed to stay on the free jetty at Sullivans Cove for 24 hours, but as our windlass was in pieces, making anchoring difficult, and as there were plenty of spaces, we emailed the people in charge and hoped no-one would mind if we stayed longer.

Why, you may ask, was our windlass in pieces? Well, for a little while now the windlass has been playing up; sometimes failing to work when the switch to raise or lower the anchor is operated. It’s possible to anchor without a windlass on a boat the size of Taurus’, in fact the anchoring part is a breeze, retrieving the anchor is the hard part. For those that don’t know, a windlass is a machine that lets anchor chain out, or brings it back in, via a gypsy or chain wheel (which grips the chain through specially cut teeth) turning on a horizontal plane. If the machine should operate on a vertical plane it would of course be a capstan, not a windlass. These devices used to operate by the simple expedient of having a good number of men turning them by hand, pushing against shafts that slotted into holes on the capstan. A fiddler would oft sit atop the turning capstan shaft, playing merry tunes to keep the sailors happy and help them forget the mule hard labour. Modern capstans and windlasses are turned via a powerful electric motor, keeping everyone much happier — until they stop working.

Ten millimetre anchor chain weighs approximately 2.5 kgs per metre. We generally anchor in about five metres of water (if possible) and we work out the amount of chain to let out with the simple formula of 15 metres plus twice the depth. So, we generally sit on about 25 metres of chain, or perhaps a little more as we let out another few metres when attaching the snubber line, the nylon line that reduces shock loading. Say thirty metres, or their abouts. Pulling in 75 kilos of chain doesn’t sound that hard does it? However, if you have ever tried dragging thirty metres of chain across a carpark, you will know that chain doesn’t drag easily. Indeed, one of the reasons people use chain in their anchoring system is because the weight of the chain as well as the anchor stops the boat from dragging.

Of course, the afore-mentioned anchor adds a further 30 kgs of steel, buried in the sand, mud, or whatever muck lies beneath the surface. Anchors are specifically designed not to release their grip on said muck without a fight. Indeed, their raison d’être is to resist all attempts to unseat them. Our 10.5 ton boat has hung off its anchor in winds of about 120 km/h in the past; it doesn’t just ‘pop out’ with a bit of a tug, though to be fair we are pulling it backwards when retrieving it, which makes it less impossible than it would be otherwise. Without labouring the point further, raising an anchor by hand is awkward, back breaking work — involving a long, heavy length of mud slick chain followed by an anchor, maybe with a hundred weight of weed attached. Ultimately, if raising an anchor by hand was easy, sailors wouldn’t spend thousands of dollars on windlasses.

Before going anywhere near the machine itself we of course checked the switch, all the connections, and all the other obvious things we could think of. Finding nothing amiss we sought advice, and were advised to try cleaning the motor’s brushes. Three out of four of the brushes were stuck so this gave us a pretty good feeling and we put the thing back together and crossed our fingers…

We didn’t stay long in Hobart as we visited the city only a couple of years ago, and have to return soon. Cara has to fly back to New Zealand for a few weeks in early April, at which time I will head into a marina in Hobart to try to get a few boat jobs out of the way. We had about a month up our sleeves, so decided to explore the greater Hobart area.

Hobart is a bit of a yachting Mecca, with nature reserves scattered all around, picturesque villages, stunning islands, and quiet secluded bays by the dozen. It is also an area that is notorious for rapid weather changes and strong winds, so we needed to maintain a certain degree of caution.

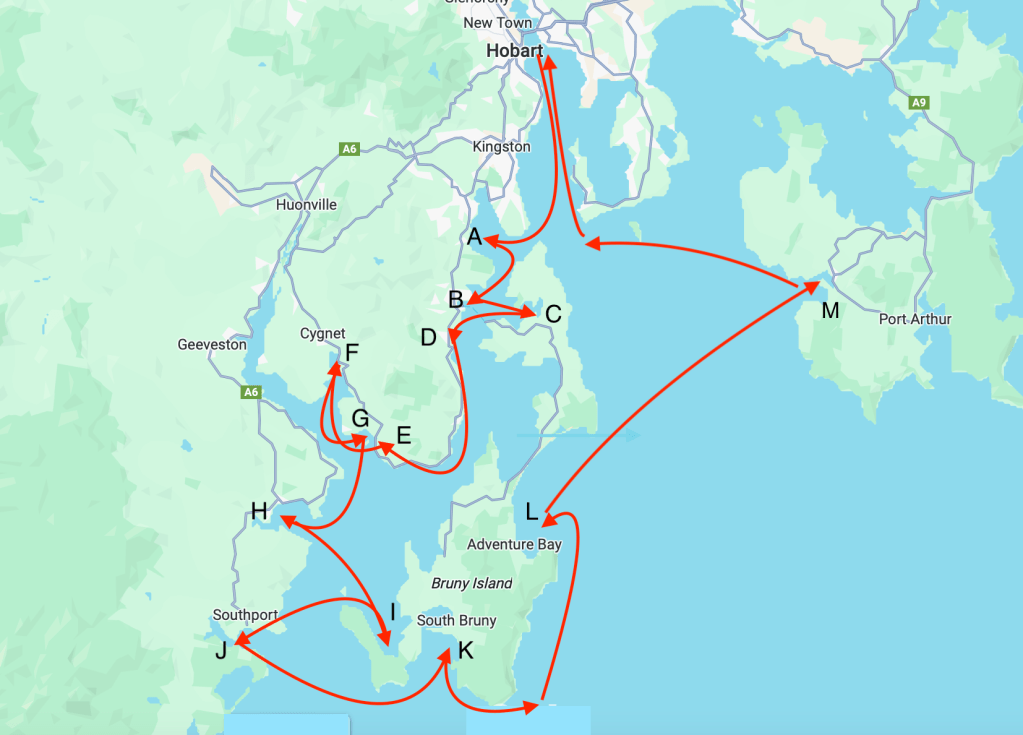

Key:

A: Snug Beach, B: Kettering/Oyster Cove, C: The Duck Pond, D: Peppermint Bay, E: Garden Island, F: Cygnet, G: Eggs and Bacon Bay, H: Dover, I: Jetty Bay, J: Southport, K: Cloudy Bay, L: Adventure Bay, M: Nubeena.

After leaving Hobart we sailed to Snug Bay, accidentally joining a race for a while on the way, and finding what has become a bit of a weather pattern ever since. We initially had too much wind, then too little, then too much, then some thunder and lightning, a bit of a rain, then no wind and brilliant sunshine. Every day is a hodge podge of a recipe with a pinch of everything thrown in.

Kettering is a lovely little town, mainly composed of a marina, and for those that follow sailing You Tube channels it’s where ‘Free Range Sailing’ spent Covid fixing up their boat. Our friends Robin and Diane, whom we met in Eden, live there, so we went to visit. The facilities in Tasmania are fantastic and once again we were able to get a free jetty berth. Later we found out that the berths with yellow strips are for loading and unloading only, the ones with red stripes you can stay on for up to three days. We were on a yellow berth. However, all the locals told us not to worry about it, so we ended up staying on the jetty for a couple of days. Which was less time than the boat opposite us, also on a yellow berth. When in Rome, and rules and all that…

Catching up with Robin and Diane was great. They are a couple that have lived life to the full and are still going strong. Robin spent years building a sustainable farm in the bush, and is the author of perhaps a dozen novels. Diane spent years sailing the world, and together they found their paradise in Cocos Keeling, an Australian island that they describe as if it were paradise. Ever generous, they drove us into town so that we could do our washing and stock up with provisions. We then got a ticky tour around the Huon Valley, an area renown for apple orchards and wooden boat building.

Leaving Kettering we headed over to the aptly named ‘Duck Pond’ on Bruny Island, or so we thought. We imagined that the near land-locked bay would give us protection from the strong southerlies predicted for the following day. Several other people must have had similar thoughts, and the bay slowly filled up over the course of the afternoon with three yachts of Taurus’ size, a trawler, and three trailer sailors calling it a temporary home. At about 6am we were rudely awakened by our dinghy, which we had angled upwards on the deck to let air in (as per a previous photo), trying to take off in about 30 knots of wind. Luckily we had tied down the front so it couldn’t get far, but as we were securing it we witnessed all the trailer sailors dragging anchor and ending up in a tangle in the northern corner of the bay. Chaos ensured as their bleary eyed crews fought to reclaim their anchors and tried to avoid colliding with one another.

Peppermint Bay was our next stop, because who wouldn’t stop in Peppermint Bay? Here we were able to sneak through the moorings and anchor close to shore in perfect protection from the strong westerlies that were due (you see what we mean about the weather). The local village, Woodbridge, was interesting to explore and had a fantastic cafe.

The following morning we sailed for about six hours, avoiding the numerous salmon farms and small ships that service them, and making numerous changes to the sails as we experienced zero wind to 30 plus knots. Eventually we found shelter behind Garden Island. A slice of paradise we thought, until we came across the “Private Property, No Trespassing!” signs. Time to go!

Moving on, we sailed up Kangaroo Bay, past Tranquil Point, and found ourselves at the town of Cygnet. There is a large mooring field in the river outside the town, and one or two boats on anchor. We decided before anchoring to attach a buoy to our anchor to mark its position. We chose to do this because the windlass, alas, was still playing up. Attaching a buoy to the anchor serves two purposes: where it is busy it can be a good idea to highlight your anchor’s position so that (hopefully) the next person who arrives doesn’t drop their anchor on top of it, or in places where the bottom may be fouled, by trees following a flood for example, it provides a way of pulling the anchor out backwards (which might also be helpful if you are lifting the anchor manually). That evening one of the drawbacks of this technique came home to us. As the wind picked up, funnelling up the valley, the yacht next to us, that seemed to have been left on anchor semi-permanently, began swinging in great arcs. We had anchored a good distance from this boat, but as its anchor rode became taut it came closer and closer, and eventually was merrily swinging right over the buoy attached to our anchor. We watched with something akin to horror. If the buoy became stuck around the other boat’s propellor or rudder it could yank our anchor free — possibly leaving us attached to this other yacht and unable to untangle ourselves. However, I was not about to go swimming in a gale under a strange boat! There was little we could do as there was no-one aboard the other yacht, and we could hardly pick up our anchor with it sitting on top of it. Sometimes the best thing to do is to do nothing. We had dinner and shortly after the wind shifted and we were able to lift our hook and move well away from this other boat. I would guess that it had at least 50 metres of chain out in five metres of water. This amount of scope may give better holding (though I have read that after 7:1 more chain accomplishes little) but it creates a hazard for others who have no idea that a boat in the anchorage is going to swing so far. I’d like to say that this is another lesson learnt, but really you can’t go into every anchorage thinking that someone may have laid out miles of chain. How would you ever anchor anywhere?

The way our windlass had chosen to manifest its ongoing displeasure was by refusing to stop when raising the anchor. The switch failed to obey my increasingly frantic thumb and I could only step back and watch as the anchor slammed home at a great rate of knots. This is probably the most dangerous situation that a windlass malfunction can result in. Researching possible causes later on we read of broken gears, snapped shaft keys, and severed fingers. The likely culprit was a stuck solenoid. This apparently happens with my brand of windlass often enough for charter companies in Europe to junk the brand item and replace it with automobile parts. These, however, aren’t rated for windlass type loads, and no doubt my insurance company would look dubiously on such Heath Robinson practices. We cleaned the solenoid’s connections and vowed to make fixing the windlass top priority.

Heading back down the river we stopped overnight at the wonderfully named Eggs and Bacon Bay. Sadly there were no eggs and bacon to be had.

We travelled south and landed in Dover. This small town shows signs of the economic woes of the region at large, at least if the number of closed shops is any guide. We parked ourselves on another free jetty for the night, yellow striped again I’m afraid to say, but all the red spots had been taken once again by fishing boats that seemed to be permanently settled there. I doubt the public jetty system was intended to subsidise the fishing industry, but as a non-tax payer who am I to complain? Two bright spots of our visit were meeting Wade and his daughters again (whom we had previously met in Port Arthur); and meeting Martin, the Commodore of the Port Esperance Yacht Club, who invited us in for a beer and gave us the code to the club’s hot showers! Cheers Martin!

Not wanting to out stay our welcome on the unloading jetty we sailed across Port Esperance’s Bay and anchored off Rabbit Island. This tranquil spot made a nice contrast to the slightly sad Dover. Many of these small rural towns appear to be kept going by salmon farming, but the number of farms and their ecological impact is causing increasing concern amongst Tasmanians. Adding fuel to the fire, the business has been thrown into some disrepute recently after a disease killed thousands of fish, and some of the corpses were illegally discarded.

With a fine southerly breeze on our beam we sailed in the morning back across to Bruny Island, weaving our way through the salmon farms again, and anchored in Jetty Bay. From here we could walk to the lighthouse at Cape Bruny at the southern tip of the island.

First lit in 1838, Cape Bruny was Tasmania’s third lighthouse and Australia’s fourth. Today, it is the second oldest extant Australian lighthouse, and the longest continually staffed. The lighthouse was built after a series of wrecks in the area. The most tragic was the sinking of the George III, a convict ship that struck a reef which now bears the ship’s name, with the loss of 133 men, 128 of them convicts. An inquiry was held after the disaster as it was rumoured that a number of the convicts’ bodies were found with bullet wounds, and had supposedly been shot by the guards whilst ‘escaping’ the sinking ship. The whole incredible story can be read here: https://www.environment.gov.au/shipwreck/public/wreck/wreck.do?key=7195

The lighthouse itself is 114 metres tall, with walls at the base over a metre and a half thick. It was built by 13 convicts (who also had to quarry the stone) in a space of 18months. Apparently the men were promised their freedom if the work was finished on time!

Cara and I were delighted to find that for a small fee we could enter the lighthouse and be given a guided tour. Our guide, Belinda, was very knowledgeable, and made the experience really worthwhile. In our travels we have visited many light houses, but this is the first time we have been able to access one.

The rest of our stay was spent pulling the windlass apart and putting it back together, kayaking, and exploring. The water is so clear that we could easily see our anchor, five metres below the surface.

Next time: we carry on sailing, and something will probably break and need fixing.

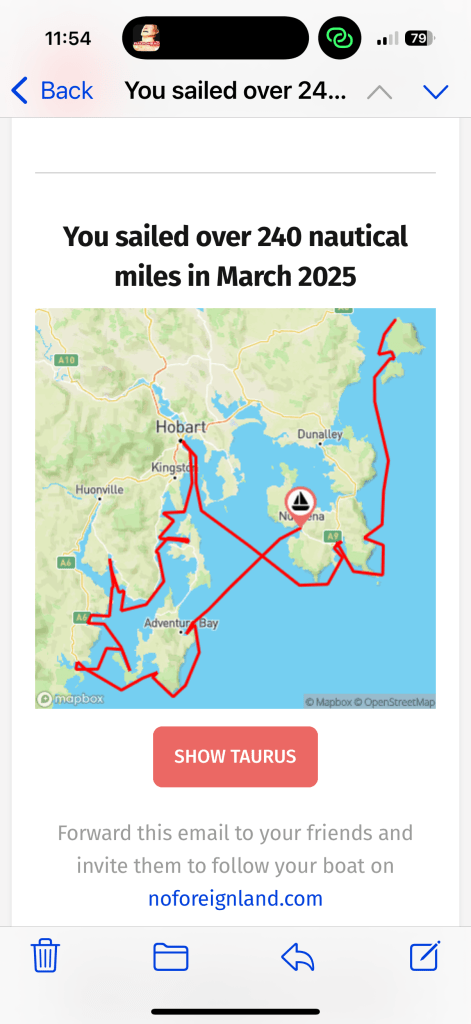

As a quick addendum, someone asked the other day about sailing apps we use, and that could be used to track us. A free app we use a lot is called ‘No Foreign Land.’ We use the app to help decide where we might anchor next, as other sailors from around the world upload anchor sites and provide reviews and information — such as the quality of holding, availability of diesel, food, laundries, and such. The app can also be used to track boats, in real time and to see where the boat has been in the past, using information taken from on board devices, such as our Garmin In-reach. Statistics can be fed back to the crew, such as how many nautical miles have been sailed in the past month. Anyway, if you’re interested have a look. We’re happy to help if you need any help or advice.

Leave a comment