Built in 1845, the largest Port Arthur building was originally intended as a flour mill and granary, but by 1857 it had been converted into a prison. One hundred and thirty six cells were available on the bottom two floors, designed to cater for “prisoners of bad character under heavy sentence.” The third floor was a dining hall which doubled as a school, library, and chapel; whilst the top floor was reserved as a dormitory for 348 “better behaved-men.”

Little of the interior of the main building is left after it was devastated by fire in 1897, twenty years after the prison closed. In the photo above you can see how small the cells were (the photo shows two floors). Note the iron hoops in the wall which prisoners would suspend their beds from (as in the photo at the start of the blog).

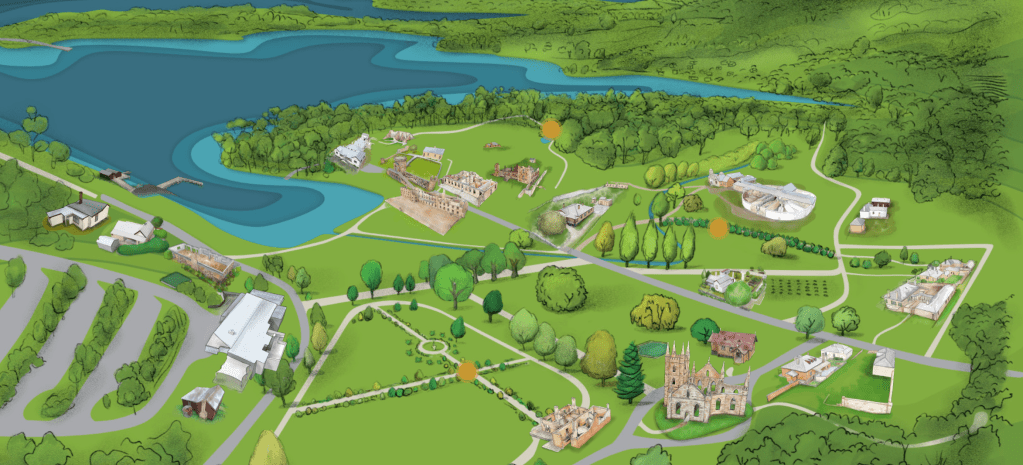

In better condition today is the ‘Separate Prison.’ This building (the circular structure to right of centre in the image below) provides an eye-opening window into what it could mean to be a prisoner in the 19th century. A visit is almost as oppressive as it is interesting. Perhaps the most jarring realisation of all is that the system, seemingly designed to inflict psychological torture, was actually intended as a humanitarian attempt to encourage reform. Based on the ‘Philadelphia model,’ the American idea was refined in Britain, most notably at Pentonville Prison which opened in 1843, and strongly influenced the Seperate Prison of Port Arthur which opened in 1849. Designed to “tame the most mutinous spirit,” the system was controversial even in its own day. Supporters termed it “the highest state of [prison] perfection,” whilst its opponents called it “an ingenious contrivance for making mad-men.”

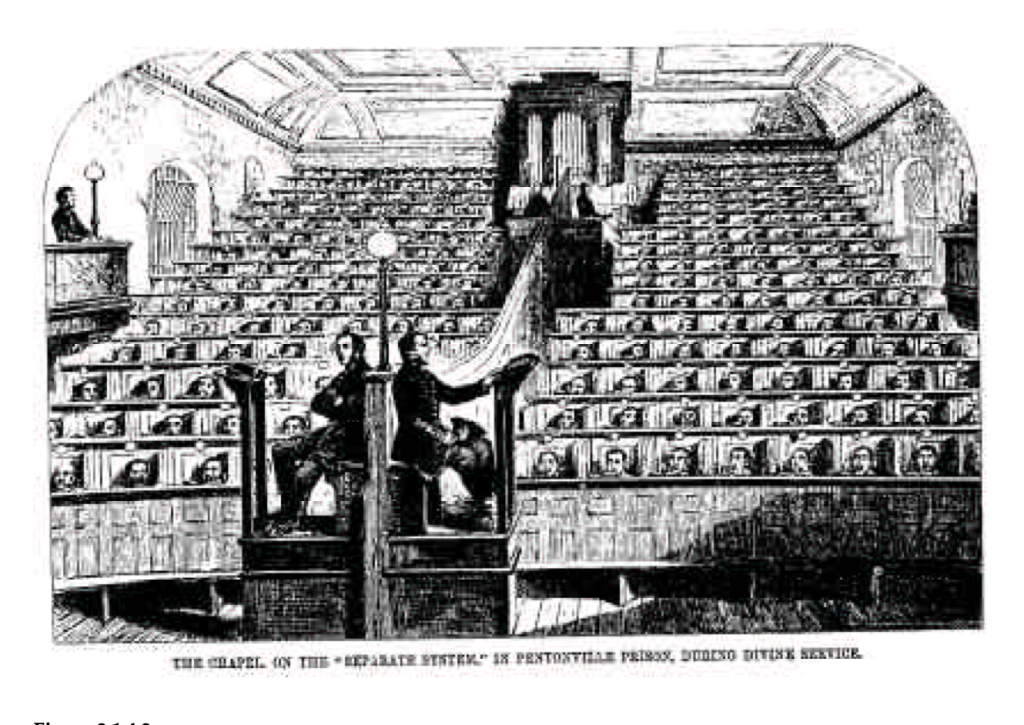

The regulations and routines suggest something of what it would have been like to have served time there. Upon entry the prisoners had their heads shaved and were allocated a number, which was to serve as their only name until after their release. The men were not allowed to speak, sing, whistle, or communicate in any other way. The only exceptions to the rule of blanket silence were permission to pass essential information to a guard, and permission to sing in chapel on Sundays. When outside their cells the prisoners’ anonymity was further enforced by their being made to wear masks. The men also had to maintain a specific distance from other prisoners, and had to turn away from their peers when in the corridors or when engaged in cleaning. The inmates naturally exercised alone, and the desire to isolate them even went so far as to require a specially designed chapel. This ensured, via the use of hinged doors, that the congregation could not see or communicate with each other, and could only stand and peer over wooden screens towards the front of the chapel.

Those who broke the rules were punished by being placed in a ‘dumb cell.’ This tiny room remains, and is entered via two doors that when sealed prevent any sound or light from penetrating. The sensory deprivation is an unnerving experience, supposedly giving the prisoner no option but to think of his misdeeds and repent. The few seconds I spent in the cell reminded me of the medieval oubliette, the dungeon cell where men were thrown to be forgotten. Significantly, Pentonville Prison didn’t feature one of these punishment cells, so Port Arthur may have tried to be enlightened — but perhaps it wasn’t as enlightened as it could have been! Apparently, some men spent up to two weeks in these spaces, fed on bread and water and allowed an hour’s exercise every three days.

As cruel as these spaces appear, it is perhaps arguable that some crimes are so heinous that they demand the most severe forms of punishment. Martin Bryant, a current Australian inmate, can only listen to music played on a radio outside of his cell, is forbidden access to news articles about his crime, and is banned from featuring in the Australian media. His crime was to murder thirty five men, women, and children in 1996 in what came to be known as ‘the Port Arthur Massacre.’ Bryant held a grudge against two of the people he murdered, but the other thirty three were tourists, mostly shot in the cafe and gift shop, apparently because their killer desired notoriety. This he achieved, but the scale of his crime prompted what had long been thought of as impossible in Australia: gun reform. The former sites of the gift shop and cafe are today memorials for his victims.

For all its dark history, Port Arthur remains a beautiful place, almost as if nature is trying to compensate for man’s evil deeds.

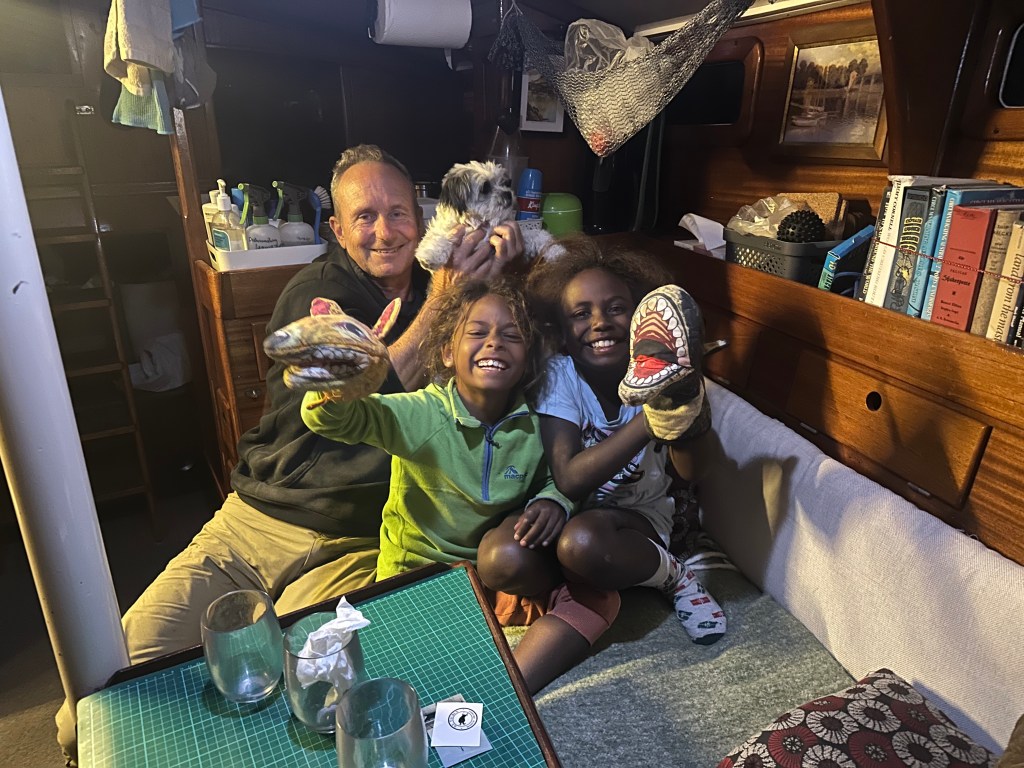

A famous Maori proverb teaches the following: “What is the most important thing in the world? Well, let me tell you, it is people, it is people, it is people.” This is certainly true in the cruising world, and the incredible people we meet are the most rewarding element in this, the most rewarding of lifestyles. We happened to bump into Wade and his daughters, Kate and Kelly at the prison, recognising them from the yacht anchored next to us. Naturally, we arranged to meet later than evening for a few drinks and an animated movie. Wade, it turns out, is a paramedic in northern Tasmania, so we had lots to talk about.

All good things must come to an end, and so it was with our sojourn to Port Arthur. Before we left we had the opportunity to catch up with Brice and Nuria on Sabre II and say goodbye. We first met Brice in the Hauraki Gulf, then in Vanuatu, and then again in Eden. Brice and Nuria are now heading north and on to Indonesia, so who knows where, or if, we will meet again?

Leaving Port Arthur we motored into Storm Bay, which, if just for this day, appeared ill named. The winds were very light, as we knew they would be, but we wanted to leave early to ensure that we arrived in Hobart in plenty of time to catch a friend of ours playing a live music set.

As we slowly made our way north we were intercepted by a pod of dolphins who appeared to be almost flying rather than swimming so clear was the water.

When the wind eventually rose we hoisted our light air spinnaker and gladly turned off the engine. We fairly flew along at 4–5 knots, imagining ourselves on the home straight of the Sydney to Hobart race.

Ultimately, the winner was never in doubt, and sailing won on the day. On arrival we dropped our sails and entered Sullivans Cove to pick up one of the free berths in the centre of town. Next to us was moored Lady Nelson, a tall ship that takes tourists for cruises.

After a quick tidy up we were off to the pub to watch our friend’s show. Sam is a professional musician who sails part time. We had met Sam and his wife, Emma, as they cruised in Norla, their traditional wooden boat, in Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia, and we had ended up arriving in Bundaberg only a few days apart. Now home in Tasmania they were picking up the strings of their old life.

After a few beers and a catch up it was home for an earlyish night, ready to explore Hobart in the morning.

Leave a comment