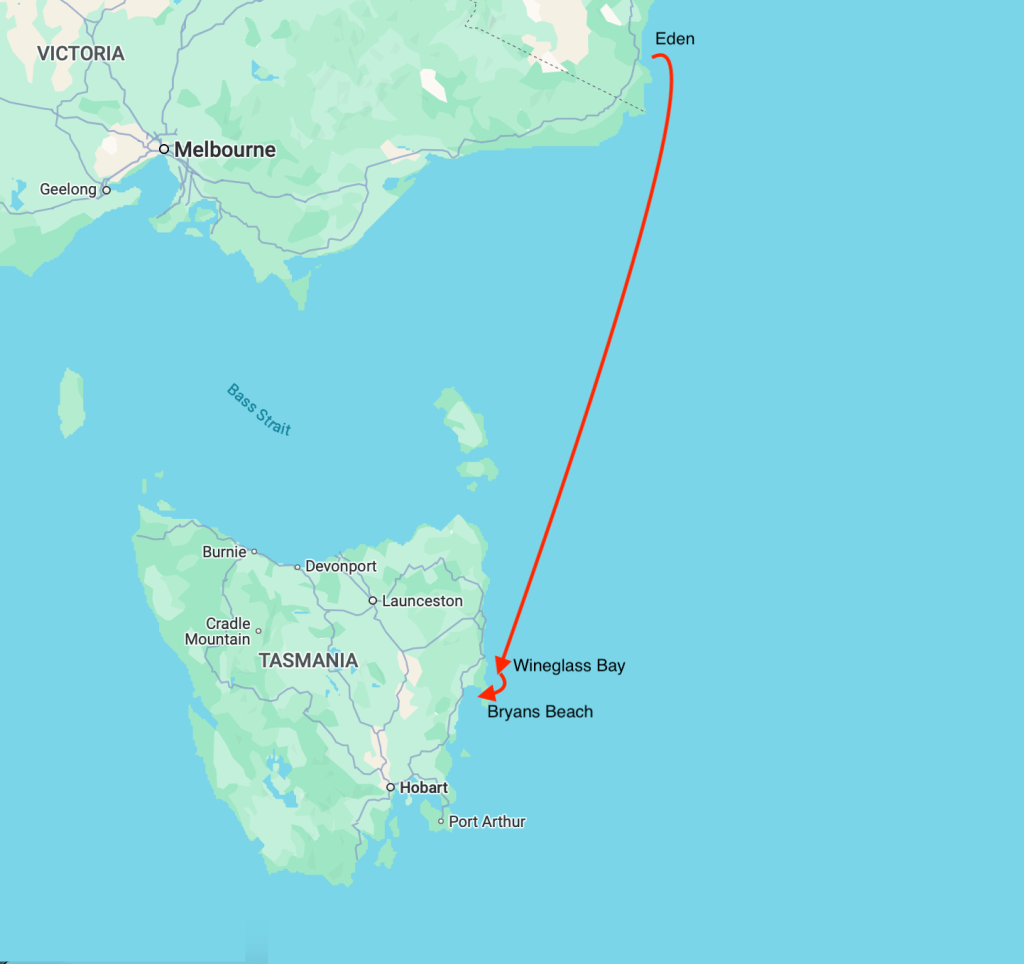

Eden is the southernmost town in New South Wales, sitting at the south east corner of the Australian mainland. This quiet, provincial town of some three thousand souls is the jumping off point for small boats intending to travel to Tasmania. Here they wait for a kindly weather window for the almost three day passage across the notorious Bass Strait.

Sitting at the confluence of the Southern Ocean and Tasman Sea, the Bass Strait is where cold air and water from Antarctica wrestles with the warm air and water from the tropics. Immense bodies of water that have circled the world unchecked are funnelled into the bottle neck that lies between the Australian mainland and Tasmania. The resulting currents are exacerbated by the rapid rise of the sea floor. Within a few short miles the depth of the sea rises from five kilometres to less than one hundred metres deep, much of the rise occurs as a near vertical precipice just off the coast of Tasmania. As the sea floor rises so the energy of the sea is forced upwards and concentrated, causing waves to rise into steep and often confused peaks.

These features mean that the Bass Strait could be described as the perfect location for perfect storms. The most famous to have taken place here occurred in 1998 during the annual Sydney to Hobart yacht race. An unusually intense low-pressure system developed, which built into an exceptionally strong storm with sustained winds in excess of 65 knots (about 120 km/h) and gusts of up to 80 knots (almost 150 km/h). The wind created waves over 15 metres tall. In this maelstrom, six sailors died and 55 required rescue; seven boats were abandoned, five of which were subsequently lost. The rescue effort, the largest peacetime operation in Australia’s history, involved 35 military and civilian aircraft, and 27 Royal Australian Navy vessels. Modern techniques have done little to tame this wild place. This years edition of the Sydney to Hobart race saw two further sailors die, and another was miraculously saved after being swept overboard and lost to the sea for almost an hour. You can understand why cruisers wishing to sail to Tasmania wait for good weather. There are few worse places to be in the wrong conditions.

Fortunately, Eden is a nice place to wait. The New South Wales Government has provided four public moorings that lie sheltered behind a modern sea-break. The moorings lie within an easy dinghy ride to shore, where public toilets and a free public shower can be found opposite the chandlery. The town itself lies atop a hill guaranteed to leave the unfit sailor breathless, but who finds him or herself rewarded with several pubs and eateries upon a successful ascent.

Another highlight of Eden is the local museum. Eden is famed for three things: for once having been considered as a possible site for the Australian capital city — due to its being equidistant from Melbourne, Sydney, and Tasmania; for being one of the deepest natural harbours in the world; and for its killer whales.

In the early twentieth century Eden was as a whaling Mecca with a difference. A pod of killer whales formed an unlikely alliance with the shore based whalers, alerting them when humpback and southern right whales were nearby, and herding them into to the bay for the whalers to harpoon. The killer whales were allowed to take the captured whales tongues, a waste product for the whalers, as payment for their assistance.

The leader of the pod came to be known as ‘Old Tom,’ a character that became so used to interacting with humans that he would sometimes tow the whalers’ boats to their prey to expedite their death, and his meal. When Old Tom’s body was found in 1930 floating in the bay, the locals maintained that he came ‘home’ to die, his skeleton was saved and now hangs in pride of place in the museum. Proudly pointed out are the grooves worn into his teeth from pulling upon the tow lines connected to the whalers’ boats.

The museum also has a lighthouse attached, but this is actually a ‘folly,’ a modern recreation built to house an original staircase, lens, and light mechanism. The one hundred step staircase used to be three hundred steps high. The lighthouse keeper would climb to the top to wind the mechanism, raising a weight that hung beneath the light and which would gradually unwind the mechanism causing the light to turn. Apparently, the lighthouse keeper would need to return to the top to rewind and lift the weight every two and a half hours.

The deep harbour allows the entry of cruise ships, and whilst we there a new floating behemoth appeared almost every day, waking everyone up with their tannoyed instructions to passengers and crew. Of greater charm were a couple of tall ships that arrived, heading home after their sojourn to Tasmania for the Wooden Boat Festival. It was disappointing not to be able to make the festival, but still exciting to see these historic vessels being used for what they were intended, and keeping old traditions alive.

We were fortunate to be in the company of a friendly and social group of cruisers who were waiting for the appropriate weather to take them where they were going. In the photo below (from left to right) we have Thomas, a Swedish solo-sailor who had just returned from Tasmania and was heading north; Ian, a professional sailor being paid to take a catamaran to Adelaide; Cara; Dianne and Robin who are from Tasmania but were heading to Lakes Entrance for a survey in the hope of selling their monohull (they prefer their catamaran); me; and Azza, the new and proud owner of the catamaran that Ian was helping him to sail home. Not featured are Brad and Rae (whose boat we are on) who were returning to Perth from Indonesia. As you can imagine, there was a lot of wisdom in the room when it came to local weather conditions, and when to cross the strait. Thomas, emphasised the need for caution, telling us that his passage across the Bass Strait back to the mainland was one of the worst trips he had had in his semi-circumnavigation from Sweden. The main issue we faced was finding a window that lasted three days. The weather in Australia has been very, very changeable, often ‘boxing the compass,’ blowing from all directions, in a single day, and rarely blowing from the same direction (other than south) for more than a day or two.

Whilst talking to more experience sailors and learning from them is incredibly valuable, we have found that the more you talk about options, the more confused the issues sometimes become, and the more you can end up second guessing yourself. Ultimately, every crew has to make their own decision as to when to go or not, and then suffer the consequences. After five or six days waiting, Cara and I thought we saw an opportunity. The weather was due to swing to the north on Friday and blow with increasing strength for three days. On Friday the wind was predicted to be 15-20 knots, on Saturday 20-25 knots, and on Sunday 25-30 knots and rising. In these situations you have to bear in mind that the wind strengths are estimates, they might in reality be weaker or stronger, and that wind gusts can be up to 40% stronger than the predicted winds. So, on Sunday we could expect winds of nearly 45 knots (85 km/h) if the forecast proved accurate. The longer we took to get into shelter on Sunday, the worse we could expect the conditions to get. To minimise our exposure we decided to try and steal a march and leave on Thursday night in light and variable winds, motoring south and exchanging diesel for distance and time.

By Thursday evening we were ready to go but the southerly refused to die. Using a weather app we could watch local weather stations report real-time conditions. We sat, staring at our phones, and waiting for the wind to drop and change direction. By 9:00 pm the trend was finally looking good, so we cast off our mooring line and motored out into the pitch dark night. As we left we met another yacht coming from the opposite direction. Calling them up on VHF we passed on the news that a public mooring was up for grabs. The skipper sounded delighted, saying that he had had a miserable passage from Tasmania and was exhausted. Great, we thought.

As we motored through the night we kept a sharp watch, knowing that the initial part of the crossing can be quite busy with ships travelling between Adelaide, Melbourne, and Sydney. Thankfully, we only saw a few ships, and all from a safe distance.

Eventually the northern wind began to blow and we were able to turn off the engine and raise our sails. The Hydrovane was tuned to our course, and successfully steered the boat 24/7 for the entire trip, using no power, eating no food, and making no complaints. As the day wore on the wind increased, and the forecast appeared to be bang on.

After an easy downwind sail we enjoyed watching the setting sun, and then settled down into our second night of three on, three off watch pattern. Starting at 9pm the night before meant that we were already feeling pretty tired. In the past we have found that it takes two or three days to get into the swing of a passage, so that shorter passages can feel like harder work than those that are twice as long.

Dawn duly appeared, and we found that despite our slow start, we were maintaining our expected 120 NMs per day. This speed would see us arrive at our anchorage sometime between Sunday morning and Sunday midday. Hopefully before the bad weather kicked in.

The wind increased as predicted and we tried various sail configurations to gain speed and reduce roll. For much of the time we had our mainsail raised in the third reef position to act as a dampener, and at one point tried a wing on wing approach, which worked well for a while.

The third and last day began wet and cold, but we were grateful to find that the strong winds we had feared the entire trip had failed to appear.

Checking the weather for the next few days we noticed that strong westerlies were predicted. With this in mind we decided to head to Wineglass Bay, an anchorage well protected from the west, but fairly open to an easterly swell. As we sailed along for what we thought were the the last few hours of our trip I made the mistake of posting on Face Book that we had almost arrived and had experienced a great crossing — counting chickens some might say…

As we approached land a pod of dolphins came to play in our bow wave, but as we enjoyed their company the wind began to rise. The closer we got to Wineglass Bay the stronger the wind got and the larger the waves became. We were now surfing down some monsters that were breaking as they rolled past, and heading straight into our supposed refuge. Knowing that the holding in the bay was described as ‘sometimes poor,’ we were concerned about how well our anchor might hold in these conditions. Given the size of the waves there seemed little chance that we would be able to motor through them if we were unable to anchor and needed to leave. Heading directly towards land in decent following seas and winds that reached almost 40 knots (39.3 knots was the highest I saw) from astern certainly focuses the mind. The greatest fear of the sailor is a lee shore trap, and we seemed to be heading straight into one.

In the photo of the chart plotter above you can see Wineglass Bay (above and to the right of the wine glass tag). As you can tell from the previous photographs the waves were following almost our exact course, straight into Wineglass, and the wind speed captured here is 35 knots. For non-sailors, 15 knots is generally considered a nice breeze for sailing, 15-20 is the goldilocks spot — not too little, not too much. At double the wind speed, 30 knots, the power of the wind is quadrupled rather than doubled, so it’s getting a bit strong. At this point most yachts would be well reefed down (their sail areas reduced to de-power the boat). If we wanted or needed to retreat from Wineglass Bay we would have to beat into the wind (sailing at the closest angle to the wind that the boat can sail) which is slow, hard work, and almost impossible in any kind of rough sea state. Attacked head on the waves effectively stop or slow the boat so much that she flounders and has to be turned down wind. With land nearby the result can be disastrous.

As we got closer to land we were rapidly approaching the point of no return. The temptation to get into shelter was pretty strong, we were both fatigued and the next anchorage was some hours away. However, we were both calculating the risks and I recall looking at Cara, Cara looking at me, and us simultaneously saying, ‘yeah, nah,’ or words to that effect. We jibed and headed back out to sea, following the line of cliffs at a safe distance.

Naturally the wind then dropped and we thought we were in the clear; naturally as we approached land again the wind began to rise. However, Boreas (the classical name for the north wind) was only teasing us, and eased again as we sailed through Schouten Passage and into the welcome protection of land. Bass Strait and the Tasman Sea had given us the merest taste of what it was capable of serving up, and we were grateful to be able to add the experience to our store of knowledge whilst avoiding any real danger.

Shortly after we dropped anchor in a beautiful spot known as Bryans Beach.

It felt like a weight off our shoulders to have arrived in Tasmania. In New Zealand, our home cruising ground is Stewart Island, an island sanctuary to the south of the South Island, an untamed wilderness home to very few people and plenty of nature. Tasmania, sitting at a similar latitude, is perhaps Australia’s equivalent, though much larger. In the nearly empty anchorage it felt like finally we had room to breathe; that the humidity was reduced to the point that there was air to breathe; and the crystal clear waters suggested that even if there are still sharks, at least you might have a chance to see them before becoming lunch.

It is funny how certain events can feel significant, whilst others do not. We had made several landfalls during our trip down the east coast of Australia, but our goal had always been to arrive in Tasmania. As readers of the blog will know, we had previously sailed here with our friends, Dave and Jackie, in their boat, Hansel; crossing the Tasman Sea from Nelson and arriving in the Tamar River after a ten day passage in the middle of winter. That trip had been pretty momentous, but we had been able to lean on the knowledge and experience of our friends throughout. Making the Bass Strait trip in our own boat, and under our own cognisance, felt like a different beast, and worthy of a congratulatory beer.

Next time: we start exploring Tasmania.

Leave a comment