We departed Sydney on Australia Day, the 26th of January, and sailed south, still hoping to get to Tasmania for the Wooden Boat Festival, starting in Hobart on the 7th of February. Our next port of call was Jervis Bay, some eighteen hours sail away at a speed of 5 knots.

Once again we raced south with the help of an easterly wind and a benevolent current, and arrived earlier than expected in the early hours of the morning. Target Beach, an anchorage in a small bay close to the heads, had been recommended as a good place to stop, so we slowly motored the last mile or so, feeling our way in the dark to the spot where our chart showed people had anchored before us.

Next morning we were glad we had been cautious in our anchoring as there was quite a swell running that turned into surf not far in front of us. A handful of surfers had camped on the beach and were out enjoying the waves. The swell wasn’t particularly uncomfortable and as the wind was blowing thirty knots outside we happily sat in the shelter of the bay. However, around midday the tranquility was shattered by a ‘gang’ of jet skiers, there’s really no other word you could use to describe them. As usual they raced around at max speed and max noise before performing a trick we hadn’t seen before. Taking these powerful and heavy machines through the surf, they turned and accelerated back towards the incoming waves, which caused them to take off and fly several metres into the air before crashing down again with a great splash.

The scene was chaotic. Several skiers would take off at the same time and land close to one another, whilst others raced around just outside of the surf line. Looking on we watched as fishermen on the rocks packed up to go home, and the surfers were forced from the water to avoid being run down or crushed. I must admit that I watched these selfish adult children with the secret hope that one of them might get hurt, which is very un-Christian of me and clearly demonstrates room for self improvement.

As the day wore on the swell increased slightly and we noticed that according to AIS (the system that allows us to see where other boats are on our electronic chart, and them us) several other boats were anchored round the corner at a place called Long Beach. Thinking that perhaps this was a better spot to wait out the wind we decided to up anchor and head around the headland, only to find that ‘the grass isn’t always greener on the other side.’

Getting to the new anchorage turned out to be a long and arduous struggle against a strong headwind, that made the engine and gearbox strain, and probably encouraged its later demise (more on that later). After an hour or so we finally crawled back into protection from the wind and dropped anchor in conditions very much like those we had left earlier.

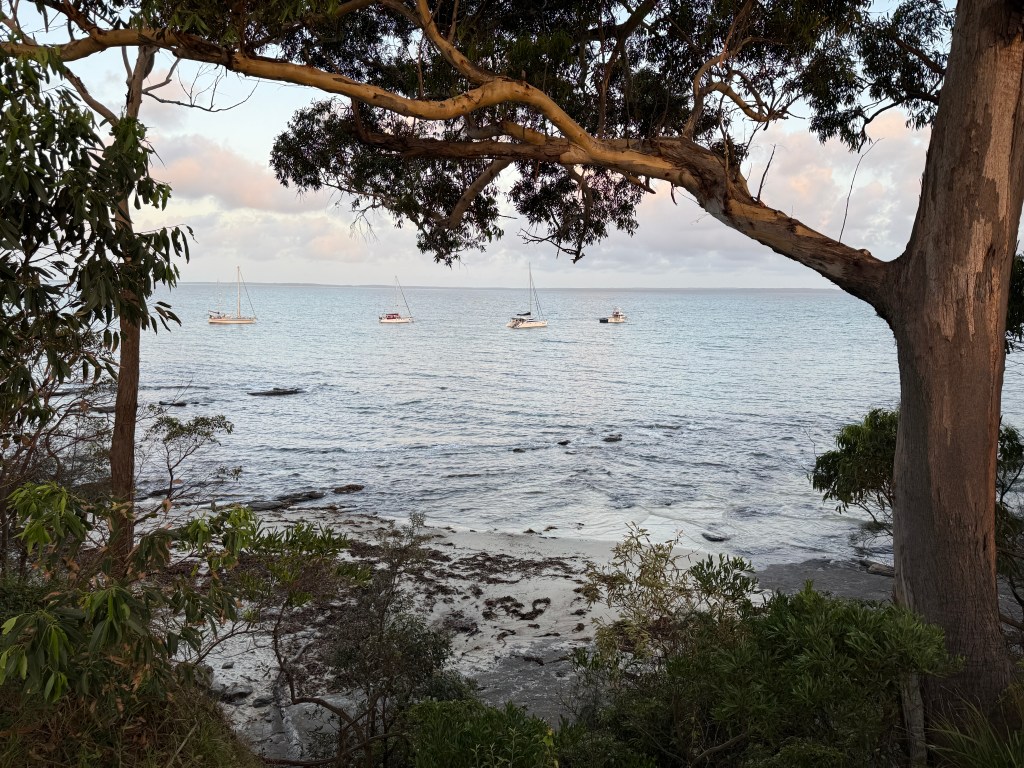

That evening the wind finally eased and we were treated to a gorgeous sunset for sundowners.

Our move to Long Beach was fortuitous in one way as next to us in the anchorage we saw a ketch that looked familiar, and it later turned out that we had briefly met Ambrosia and her crew in Vanuatu. Guy, Cassie, and their daughter, Rona, hail from the States but had emigrated to Tasmania and were on their way home. These guys would later save our skin.

Next morning a light breeze was blowing from the north and as we had plenty of room we took the opportunity to sail off our anchor. Yachts don’t really ‘need’ engines, and people like Josh Slocum, Lin and Larry Pardey, and many others, have circumnavigated the world without one, but as engines became cheaper and more commonplace so skills have degraded, and as the average boat has increased in size, and the average crew aged, so modern sailor’s reliance upon them has increased. It would be a rare yacht today that ventures out without an engine, and many people look upon the lack of one as irresponsible and unsafe. Certainly engines make it much easier to manoeuvre a yacht, especially one of a decent size, at slow speeds, and can be a massive boon to safety when the wind pipes up and a lee shore lies nearby. Without one you have to be much more careful about where you go and when, and yet the ambivalence they encourage can be misplaced, because engines can fail.

We sailed south enjoying the light winds, but strong gusts of over 30 knots suddenly blew up making us scramble to reef and maintain control. At one point when trying to ease a sheet I succeeded in creating a riding turn, a situation in which a line (rope) wraps around itself on a winch so that it can’t be released or eased. The solution is to take the strain from the line, normally by attaching another line with a rolling hitch to the first and taking this to another winch which takes the burden. However, in light winds one can often manhandle the line oneself, which is much quicker. As the gust died this is what I tried to do, but as I took the load and released the riding turn the wind suddenly picked up and ripped the line through my pudgy fingers. In this situation if one doesn’t immediately let go a friction burn is the result. Despite knowing this my automatic reaction was to try and grip the rope harder. We seem to be hardwired to think that because we could hold a rope we can continue to hold said rope, the fact that the line is suddenly under two or three times the load takes a critical moment to register. As so often in life, pain is an excellent teacher, making evident lessons that we really should have known already.

The treatment for burns is to cool them, and friction burns are no different. Luckily, due to Cara’s good management, we have an ice pack in the fridge and this was soon put to use, followed by numerous ice cubes that had to be constantly renewed to keep the stinging away. One handed crew members in gusty conditions are not of much use, but we managed to make it safely to our anchorage and happily dropped the hook.

Later that day, the crew from Ambrosia came to visit and offered to take us to shore in their dinghy, ours still being lashed to the deck as we planned to leave the next day and were too lazy to undo it. We tootled into Vincentia and wandered into town to visit the supermarket before being given a lift home.

In the morning the weather looked kind for a southerly sail, so we packed up Taurus and preceded to head out of Jervis Bay. The wind was about 15 knots from the east sou’ east (changing to an easterly later) and we were happy to sail in the company of a tall ship leaving at the same time, no doubt also heading to Tasmania for the festival. As we left there was also a couple of naval vessels departing (the Royal Australian Naval College is based in Jervis Bay) and even a Hurricane C130 overhead. The radio chatter made it clear that that there was a big Search and Rescue training exercise taking place.

Trying to sail we headed off shore to get a better angle to head south. We then turned and had a fairly narrow angle of sail which we would have to carefully manage until we got past a nearby headland. As we approached the wind died and prudence dictated that we run the engine to keep a safe distance from the rocks whilst maintaining our heading.

With the engine running I thought I heard a ‘funny noise’ and whilst I was listening to see if I could identify the issue, Cara pointed out that though the engine was on and we were in gear, we weren’t actually going anywhere. With the headland looming we made the call to about turn and sail back into Jervis Bay with the aid of the easing wind. Once again, prudence reared her head and we decided to call up the NSW Marine Rescue chaps to let them know that we didn’t need assistance, but that the situation might change if the wind died completely. It is generally a good idea to open channels of communication early if situations start to head south, so that if they really go pear shaped response times can be much faster.

Before long we were back in sheltered water and making progress to an anchorage. Cara was ‘steering the cutter’ (well sloop) as I lay on the hot engine fiddling with the gear select lever to make sure that forward gear was actually being engaged. This was about all I could think of as an immediate action to try and remedy the problem, and it didn’t work. My next step was to phone a mechanic friend in New Zealand, and here I found one of the problems with activating the good services of Marine Rescue. Whilst I was talking to my friend they tried to call me so I declined the call. They then called back, and back, and back, and back until I had to end my call to my pal in New Zealand to tell them that we still didn’t require assistance and were still under sail. The nice man told us that a boat was coming to meet us anyway. A few minutes later a powerful launch with about six crew members arrived and took station off our port side. We continued to try and work out our issue, but our speed was painfully slow, and the resource that we felt we were tying up made what wasn’t a problem feel like a problem. We looked at the Marine Rescue staff and they looked at us as we ghosted along at a knot and a half. Ultimately, we kind of got peer pressured into asking if they wanted to give us a lift. To be fair, if the wind died completely before we got to the anchorage we would have needed a lift, but at this stage we were still moving.

The first thing the Marine Rescue guys yelled back was ‘do you accept all liability,’ which seemed an odd thing to say at the time. ‘Sure’ we replied, not knowing what we were letting ourselves in for. Rather than tow us from in front, the launch came along side. We lay our fenders out and made bow and stern lines fast, at which point the launches skipper, possibly late for lunch, increased his speed and we took off. As the speed grew a bow wave was created which encouraged the boats to ‘work’ against each other, and caused the fenders to move and pop out from between the boats. This led to the rough rubber surface of the launches inflatable hull rubbing against our paint. We struggled to get the fenders back in place, realising too late why liability had been an issue. Still, as I said, we might well have needed this lift had the wind dropped further, and I wouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth if it hadn’t been for what transpired later.

Marine Rescue deposited us on a public mooring off Huskisson, a touristy town named after William Huskisson (1770-1830) who was destined to be run over by The Rocket, thus becoming the first person to be killed by a train. The fortune of the town’s most famous son could perhaps have been taken as an omen.

The moorings at Huskisson are only protected from the south, and a long swell almost continually rolls in from the bay’s entrance to the east. The public mooring buoys are quite large, perhaps a meter in diameter and a metre deep (photo below). Normally with mooring buoys the thing to do is to pull them up nice and high so that they are under tension and can’t rub or bang against the hull. However, the depth of the buoys and size of the swell meant that even when hauled up as far as possible they were lifted by passing waves and then dropped back down with an almighty yank and a crash — over and over again. Having tried, and failed, to sleep through this constant jarring and noise the first night, we let some slack out the following day and were woken in the early hours by a different crash. As the swell subsided the buoy floated around Taurus’ hull and smacked against it. A boat’s hull acts a bit like a drum, so the noise created by a fairly mild knock can be pretty loud and alarming, and the force, if not gentle, can chip paint or even dent steel. This alternate pulling up and letting out of the mooring buoy to try and find a semblance of peace was one of the hallmarks of our stay at Huskisson, one of the most uncomfortable anchorages I have ever had the misfortune to visit, and this in pretty mild weather. Only one other boat stayed for a night whilst we were there, and they disappeared first thing the next day. Should I ever have to have to stay there again I think I might follow William Huskisson’s lead and throw myself in front of a train.

Of course, we weren’t at Huskisson for giggles, but rather to try and work out what was wrong with our drive, and if possible fix it. The problem was pretty clearly the gearbox, so we phoned up a few places and found that overhauling our existing unit would cost about $3,000. Another phone call to the manufacturers elicited the information that a new gear box would cost us $4,000 delivered. As the old gearbox probably dates to 1995, when the engine in Taurus was last replaced, the new option seemed the obvious way to go. Thankfully the manufacturers had a new gearbox on the shelf in Sydney, so we only had to work out where to have it sent. Fiddling with prop shafts in boats (the gearbox is attached to the prop shaft) whilst they are in the water can result in terrible things happening. In the worst case scenario the shaft can back out of the boat, letting in a deal of water and potentially sinking her if the hole can’t be blocked. Because of this (and other issues like stability, ease of access to hardware shops, and so on) most people would prefer to tackle this kind of job on the hard. However, putting a boat on the hard is not an easy proposition in rural Australia where small tinnies are the general rule, and if the facility exists using them comes with some pretty stiff financial costs. In the past we have been quoted $450 for the lift out, the same again for the lift back in, and up to $250 per day for a cradle.

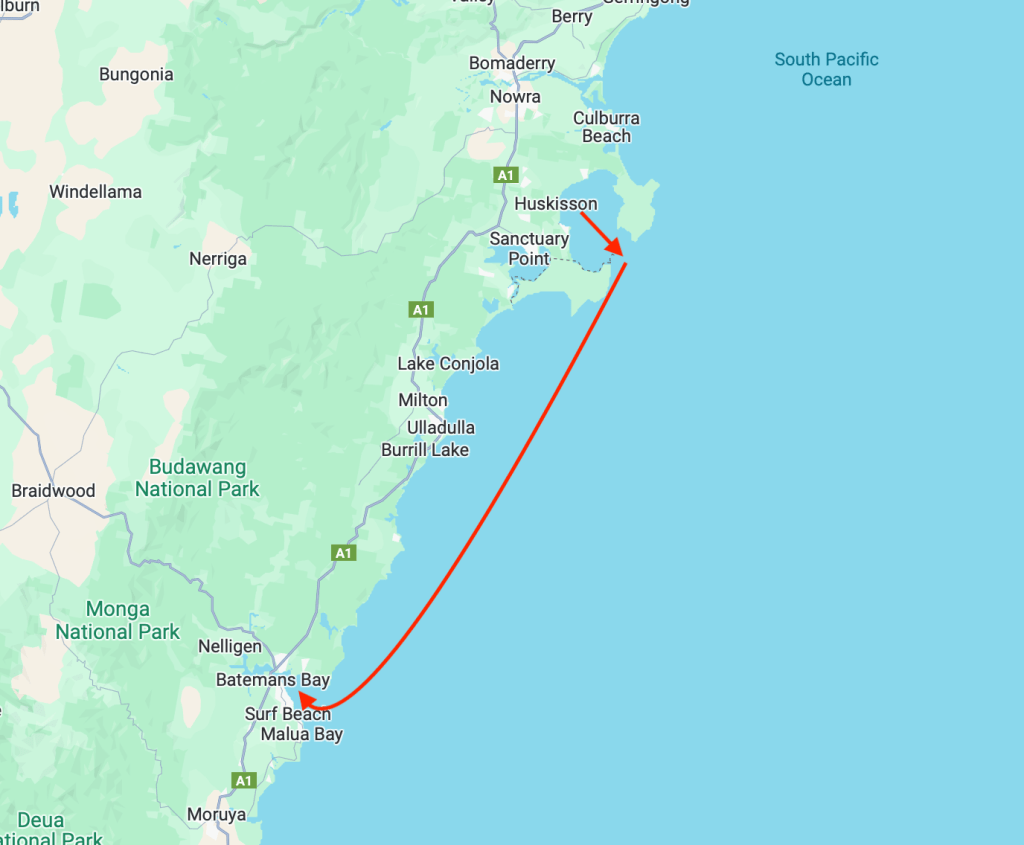

In Jervis Bay, however, there were simply no facilities for us to access. It was not only impossible to get Taurus out of the water, but also to find a berth, or indeed anywhere with decent protection from more than one direction. As we discovered that we would have to lift the engine to remove the gearbox (the gear box is bolted on to the inside of the bell housing, which also features the rear engine mounts) there was no way in hell I was going to try and undertake the job on our super rolly mooring where just living was tough enough. After making more enquiries we found that Batemans Bay, about twelve hours to the south, had both a marina and a haul out yard.

We next had to wait for a weather window that would allow us to sail to Batemans Bay, and work out how best to get off the mooring. The latter was challenging because we would probably have to leave in a northerly, a wind that would create a lee shore behind us. Nearby to the west were shallows, a bar, and a reef; to the east lay space, providing we could get beyond the rocks that curved northwards from the end of the Huskisson beach. Adding to the complexity were moorings and the potential of boats being moored to either side of us when we wanted to go. Essentially, we had to be able to gain way immediately we left the mooring. Otherwise we would have to turn downwind to gain speed and steerage, almost certainly having to slip behind a fishing boat on a mooring to the east, a course that would take us perilously close to the beach and rocks and that would give us little in the way of a Plan B if things didn’t go well. Our confidence wasn’t boosted when we were told that the ground in the area was shale over rock, so that our anchor might not hold if we needed to deploy it.

Ideally, we thought, we would get a tow for the few metres required to see us past the moored boats and the rocks to the east. A mere hundred metres or so. With this in mind we mentioned it to the chap at the Marine Rescue base when we popped in to thank them for their help. We also wanted to enquire about becoming members of the Marine Rescue service. We have been long term members of the NZ Coast Guard, which assures free assistance if needed, where as non-members are billed. Australia’s Marine Rescue is a different beast. Far from being a national service (as it is in NZ) Marine Rescue is state funded but functions via individual bases. This, we were told, means that if one base has an excess of volunteers they are not allowed to help out at another base that might have too few, or might have been hit by sickness. To those cruising the coast or country this approach might seem less than ideal, but as the service is state funded and free to the user it doesn’t really matter, apart from making membership a bit pointless. We have since been told that membership can confer a better quality of service, but this is far from guaranteed.

The Marine Rescue guy we spoke to was helpful and told us that we should be able to get a lift on either Saturday or Sunday as the patrol craft would be heading out anyway. Relieved, we did a few jobs, like fixing our 8hp outboard motor, and then a few touristy things, like visiting the Maritime Museum.

The maritime museum turned out to be excellent, especially the display of antique survey gear, sextants, and Napoleonic War weapons. For a fan of Patrick O’Brian, C. S. Forester, and Frederick Marryat, the latter was very interesting and right up my alley.

During our fact finding sessions regarding where to go, and how to fix our problem, Cara had made contact with local sailors who, after offering advice and assistance, kindly invited us to dinner. Dan and Liz, and Ross and Janet, have been building their own catamarans for several years, and whilst we won’t hold that against them, we hope that they see the light and get rid of an extraneous hull each. Five minutes with an angle grinder should do the job perfectly — two monohulls for the price of one cat, and an immediate boost in street cred and aesthetic appeal.

But seriously, those interested in boat building, especially the process of building a cat, should check out Ross’ You Tube channel, ‘Life on The Hulls,’ for great tips and advice.

Having checked the weather we revisited the Marine Rescue centre to tell them that Sunday looked good for us to leave, and to ask what time might be convenient for them to help us. Our reception seemed much frostier this time around. We weren’t allowed in the building, and the person we spoke to on the phone said he would have to talk to his supervisor about our request. When we phoned back later we were told that they couldn’t assist us.

Next day dawned fine with a ten knot breeze from the north. We got ourselves ready to go, by which time the wind had increased to 15 knots. Working out our tactics it seemed a good idea to keep the Marine Rescue guys abreast of what we were doing. We spoke to a new person who encouraged us to wait so that he could talk to his supervisor to see if they could in fact help. We were reluctant to delay as the wind was increasing, which would help us gain way, but also increased the risk of being blown onto the lee shore. We were promised that he would have an answer within quarter of an hour. Fifteen minutes later we were told that the supervisor was on a boat coming out to see us.

A short while later two Marine Rescue jet skis turned up. We had no idea what they wanted but they asked us the standard questions that Marine Rescue always ask, length, draught, and weight of vessel, number of persons on board, and so on. Having answered these questions a launch appeared with the supervisor, and we had to repeat the same information all over again. On hearing our weight, 10.5 tons, the supervisor said, ‘we can’t tow you, our maximum is 7.5 tons.’ As we had provided this information at least four times to local staff we weren’t too impressed by having been asked to wait for the supervisor to announce what was obviously a foregone conclusion. If the conversation had ended there we would have retained more respect for the guy’s judgement, but unfortunately he kept talking. He informed us that if they tried to tow us we would drag them onto the rocks. How this would happen is difficult to imagine, we only wanted an assisting tow to get going, and surely if the critical situation he described should arise they would be able to cut the tow line? The decision having been made it didn’t seem worth pointing this out. He then said that the jetskis could hold station with us, and if we were swept on to the beach we could jump into the sea and be rescued by them. I was so shocked by this vision that I think my jaw literally dropped open. Then, seeing our 8 hp outboard on the rail he asked why we didn’t attach it to the transom instead of asking for a tow. Trying to hog tie an outboard to a yacht’s transom is a good way to have a nasty accident, and almost certainly lose the motor in the process. The man suggesting this was the local Marine Rescue Operations Manager, standing on a launch with two massive outboards, providing, I would guess, something like two or three hundred hp. Somehow he had arrived at the conclusion that whilst his boat didn’t have the necessary power to help, our 8 hp motor could be jerry rigged to do the job. As if to prove that he knew absolutely nothing about yachts or sailing, the guy then asked why we didn’t wait for the wind to die — ‘because our engine doesn’t work’ we said in bemusement. More prosaically he then asked why we hadn’t booked a mechanic or a tow from a commercial operator. We replied that we had tried to speak to several mechanics, only one of whom had gotten back to us, to tell us he couldn’t look at our job for months. We added that we hadn’t investigated a commercial tow because we weren’t sure we needed one, and we had been told on Friday that Marine Rescue would be happy to help. The conversation clearly wasn’t going in a helpful direction. Having asked where we were heading the Ops Manager said something to the man at his helm and in a fit of what appeared a lot like pique he zoomed off, taking his jet skiers with him, and leaving us to face the peril of being ship wrecked alone.

Having messed around long enough we hoisted the main, pushed it around so that the boat was pointing in the right direction, let out the jib, and began to sail. Running forwards I released the mooring line and we were off and sailing. It was just as easy as it sounds. Though very slow to start with we were able to maintain our direction, and as our speed increased we knew that we were perfectly safe and really shouldn’t have bothered with all that Marine Rescue palaver.

We repeated our trip out through the heads, turned south and enjoyed another fast ride in the 15-20 knots and strong current, arriving at Batemans Bay at about 8:00 p.m. just as light was fading. Getting into the anchorage, behind a reef, was a bit of a game, involving some stressful tacks in light winds due to the shelter of the headland. Taurus needs some speed and momentum to tack (turn the bow across the wind), and if she doesn’t have it she’ll go so far and refuse to turn any further. The danger of this situation is that the boat can end up ‘in chains,’ that is head to wind and stalled without steerage. Once again, the need to practice anchoring and slow speed manouvering without a motor was brought home to us.

To anchor without an engine one simply has to reduce sail to slow down and then turn into the wind to effectively stop the boat. When the boat stops the anchor is released and the boat is blown back by the wind. More chain is released until the desired scope is out, we use 15 metres plus twice the depth of water, and then the chain is snubbed off. Job done.

Anchoring without an engine isn’t then particularly hard, in good conditions with plenty of space, but being able to do it accurately takes practice, and I’m sure doing it in less than ideal conditions would be an entirely different kettle of fish.

Northerly winds had been forecast for the next day, but they failed to appear. The marina booking lady had told us that the marina staff would be able to assist us with a tow to get in, but after we spoke to them this proved not to be the case. We were a mere 2 NMs from the marina, but between us and it was yet another bar. The bar on the Clyde River is particularly shallow and we needed to cross it close on high tide, which was just after midday. Given the lack of any wind and the very calm sea state we decided to try and tow Taurus with our newly fixed 8hp outboard. Towing a boat of Taurus’ size isn’t inherently difficult. You aren’t after all trying to pull ten and a half tons, most of that weight being supported by the water, so in calm conditions it is pretty easy for an individual to pull Taurus around by brute force, say when moving her forward or backwards on a jetty. We have heard of boats being towed by someone swimming (that guy or gal must be a hell of a swimmer) or by a row boat. So, whilst we knew the practice wasn’t impossible, it was a technique that we had never had to learn. Essentially the outboard goes on the dinghy which is strapped to the beam (the side) of the boat. The engine provides power and is locked in a neutral helm position whilst the boat is steered from the main wheel. Like most things, practice makes perfect. Our first attempt saw Taurus swinging in circles that we were unable to control, possibly due to a current. We then tried towing in the normal car-like-fashion, but whilst we started in a straight line the boats kept diverging onto different paths that were difficult to realign. We then went back to having the dinghy tied to the beam in a slightly different configuration and found moderate success!

As time was critical, due to the tide, and it looked for a while like we would be unable to tow Taurus adequately, Cara called the Batemans Bay Marine Rescue to see if the staff there were of the helpful or unhelpful variety. As soon as she began to explain the situation the person on the end of the phone cut her off, telling her that there was a note on their desk from the Operations Manager at Jervis Bay stating that they were not to help us. It appears that the Manager in Jervis Bay had asked our destination not out of any concern for our wellbeing, but to forestall any request for assistance we might later make.

Having got Taurus moving we decided to keep going. The unknown bar was ahead of us and if there were any waves we would be completely stuck, so we found the number of a commercial tow operator and gave him a call. He reassured us by telling us the bar was like a millpond and suggested that we keep going if the boat was moving. He added that he could be with us in twenty minutes and that the fee would be $350.

Now, I understand that some people would say that we should just stump up for the services we need, but we, like many cruisers, do not have unlimited funds. If we had gone the way of commercial operators for every difficulty our latest escapade would have looked something like this: to get off the mooring in Jervis Bay – $350; to get into Batemans Bay Marina – $350; to go onto the hard for a few days – $2,000; for a mechanic to swop the gearboxes – $2,000–$2,500 (diesel mechanics charge around $100 per hour, the job took us three days). Time is a seperate factor, but also expensive. The wait for a mechanic is several months long at the moment (and many mechanics simply can’t or won’t work in the tiny space around Taurus’ engine), as such we would have had to stay in the marina at $107 per day for however long it took for them to do the job, say three months – $9,500. You get the idea. Paying someone to fix our problems has to be a last resort, and, to be frank, often the job you pay someone to do turns out to be poorly done.

We struggled on, and it was at this point that Guy from Ambrosia appeared in his dinghy with his 10 hp outboard to give us a hand. Tying this onto the opposite beam more than doubled our available power, and we shot ahead at around 3.5 knots. The bar was as described, very flat and shallow, but no great hindrance. Our next challenge was to turn ninety degrees into the marina, and then make a second ninety degree turn to access our berth, whilst more or less simultaneously getting Guy and dinghy out of the way before ‘landing.’

Our first attempt to turn into the marina failed due to the strength of the current, but whilst I thought we would have to anchor and call the tow man, Cara simply swung us around 270 degrees, entered the marina and had us lined up with the jetty. Guy was rapidly released and just like that we were tied up and safe. Looking down the jetty we could see two Marine Rescue boats, once again with horse power to burn. We had towed ourselves with a total of 18 hp, so it was hard to credit that one of these boats with several hundred horse power couldn’t have helped us.

Now let me be clear. I can understand that the NSW Marine Rescue stance might be that they will only respond to situations in which lives are at risk, and that operations of a non-critical nature should be handed off to commercial operators due to cost, issues with manning, and so on. If that is the case the position is not advertised, and was never stated to us. In New Zealand if you need a tow then the Coast Guard will provide it, to ensure safety of crew and craft, avoid environmental issues, and so on. I presume it’s the same here. The reason we had been refused help in Jervis Bay was because we were ‘too heavy,’ not because our request fell outside the service’s remit. The reason why we were refused help in Batemans Bay is unclear and I have written to the service to clarify their position. It appears that our decision to keep the service informed of our intentions, as a responsible safety measure, served to preclude us from being able to access assistance because the Operations Manager in Jervis Bay took a dislike to us. If this is the case it’s hard to imagine a more irresponsible and unprofessional act. Intentionally excluding a disabled vessel from being able to access assistance, without knowledge of the circumstances in which aid has been requested, goes against every tenet of the sea, let alone the duty of a manager in ‘Marine Rescue.’ Hopefully we will be able to avoid any further need of Marine Rescue’s assistance, I would certainly be loathe to ask for it.

That afternoon we began stripping out our gearbox, but that tale will have to wait for next time!

Having to sail without an engine was an interesting, if stressful, experience, and certainly demands greater awareness and skill. I hope that when our engine is fixed we won’t forget the need to keep practicing the skills required when an engine is unavailable.

Leave a comment