Before leaving Amedee Island we had an opportunity to catch up with Rob and Kim from Sweet As, who we had last met at the Blue Lagoon Cave in the Ysawa islands in Fiji. Together with Karen and Dean from Run to Paradise, an Australian couple returning home after cruising in Japan and Alaska, we took our dinghies ashore and set up camp on the beach to enjoy the sunset and some cold drinks. We had been warned about the number of sea snakes that we might encounter on the island, but not having seen any we weren’t overly concerned.

However, the sea snakes obviously like sundowners too, and soon crashed the party. The snakes are actually kraits, which are ‘oviparous,’ meaning that they go to land to digest prey and lay eggs, as opposed to true sea snakes which are ‘ovoviviparous,’ or fully aquatic. Thankfully, the highly venomous kraits are docile and non-aggressive. As the sun prepared to set we were inundated with four or five slithering backwards and forwards, one even slithering over my foot. When someone says ‘don’t move!’ on a snake infested beach they certainly grab your attention!

We didn’t linger once the sun had gone down and returned to our floating refuges. That night, however, the wind changed direction and picked up, and the boats without any shelter jerked hard on their moorings as they rose and fell with the waves. It was horribly noisy and uncomfortable, and Cara and I were up at first light to cast off the lines and head back to Noumea for some sleep. We had a great sail back in the fresh breeze. Although we had planned to anchor out we couldn’t find a free spot in the crowded mooring field / anchorage, so succumbed to the easy option and returned to the marina.

After a lazy day and a good sleep we headed into town to return a soda stream bottle that that turned out to have the wrong thread for our machine. The language barrier made things awkward until a young woman who spoke excellent English came to our rescue. Yolande had been taught English by an Australian manager at the mine where she worked, and was particularly proud of her ability to swear which she did like a true native Australian! Because the store would only refund money by transferring it into a bank account, Yolande offered to let us use her account and gave us cash from her pocket (she actually gave us too much and wouldn’t accept anything in return). This generous young lady then drove us across town so that we didn’t have to walk so far to visit the aquarium. During the drive I asked what she thought of the current troubles. She told us that she was very angry with the rioters, which had caused her to lose her job when the mine was closed. A Kanak, indigenous islander, she wanted to stay under French rule, though her mother, who was also with us, was a keen supporter of independence. Such is life in New Caledonia at the moment. Yolande’s ambition was to emigrate to Australia if she could get a working visa. New Caledonia seems fated to lose some of its best and brightest if the troubles can’t be resolved.

As we were too early for the aquarium, and it was very hot, we found a nice watering hole where we could hydrate, which is very important. On days like this we can hardly believe how lucky we are to be able to enjoy this lifestyle.

The aquarium was well worth a visit. Many of the tanks had a kind of magnifying attribute built into them which created some interesting optical affects. The people were almost as much fun to watch as the fish.

The trip to the aquarium was the last of the things we wanted to do before leaving Noumea, and with a weather window looking good in a couple of days we buckled down and did all we could to get the boat ready. This involved giving away food stuffs that Australian Customs would seize, checking the engine, stitching another patch on the jib where the material was getting thin, fuelling up the diesel tanks, and so on.

Saturday the 26th of October saw us doing the last bit of provisioning at the local market before saying a fond farewell to New Caledonia. We had thoroughly enjoyed our stay and hope to return some day.

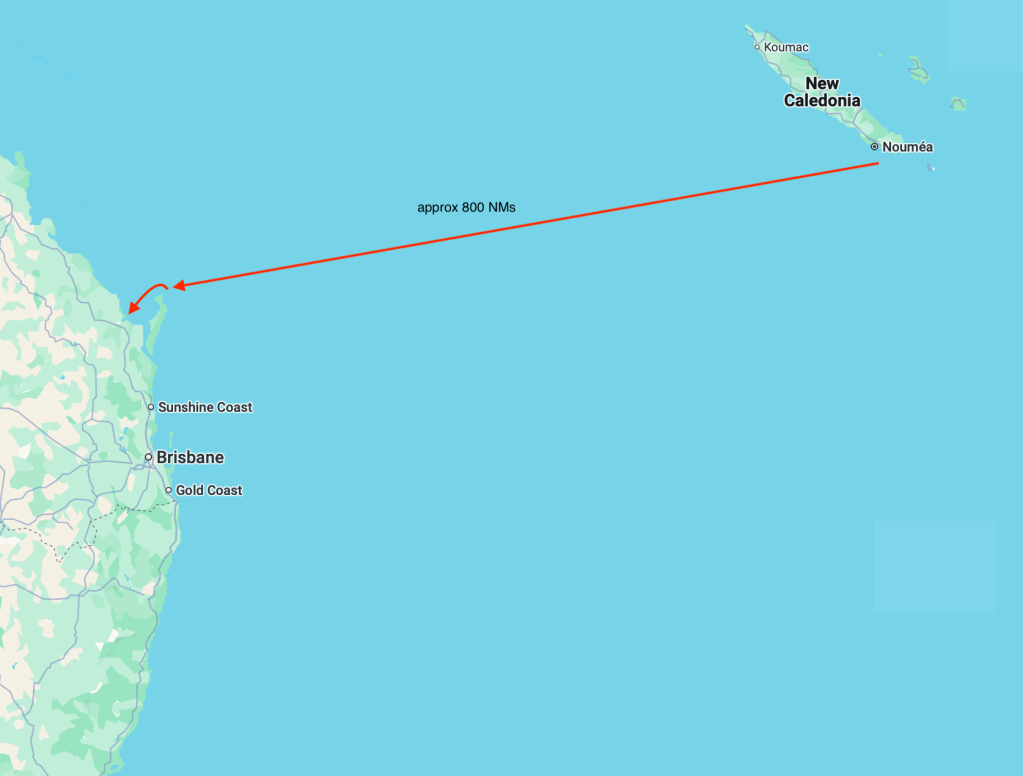

The forecast was for several days of winds in the 10-15 knot range from the south east. Naturally, when we came to leave the wind was blowing from the west — the direction we we wanted to head in. Happily, we were able to divert to a sou’westerly passage in the reef, near Amedee, so we were able to sail. Once through the skirting reef we set the Hydrovane and settled down for the seven day passage. Apart from a day when we had no wind, the Hydrovane was to steer the boat near continuously for the next seven days. This simple piece of engineering uses no power, makes no noise, and yet keeps the boat reliably on course. We are still learning the intricacies of getting the best out of it, and it’s sometimes a PITA to set up, but I don’t think any cruising boat should be without some form of wind steering.

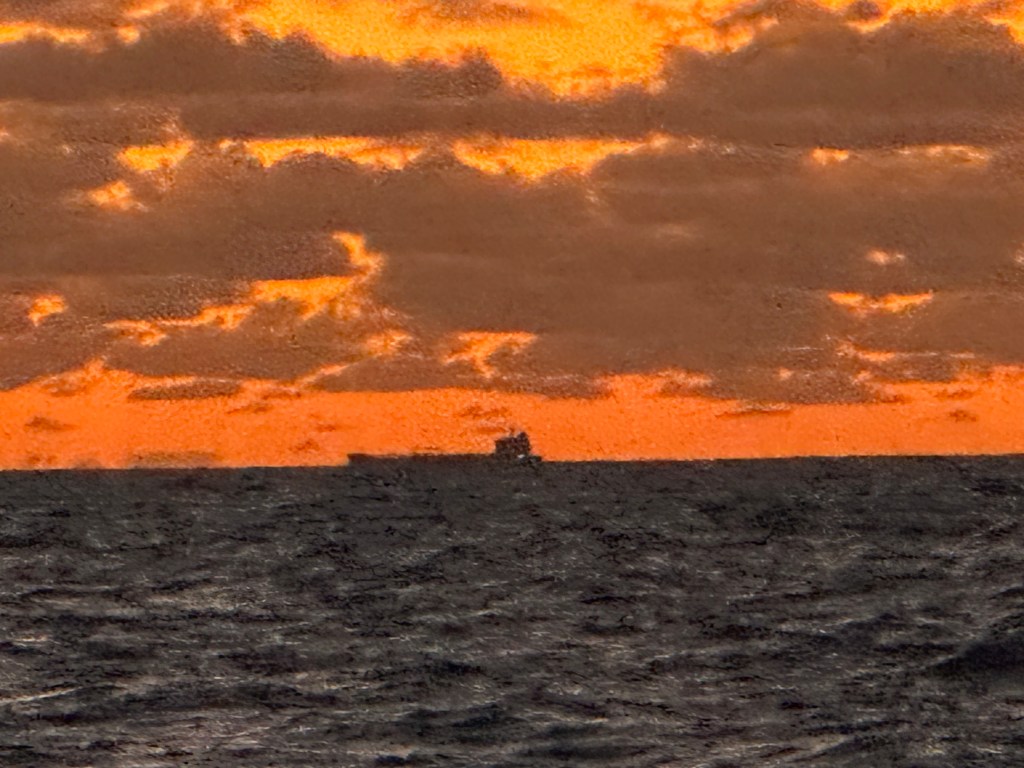

Later that evening we had to pass though a region marked as having a few FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices). We had never seen one of these, but had heard a few horror stories from other yachties who had collided with unlit FADs at night. I kept a lookout and was rewarded by finally seeing one of these floating hazards.

The chart warned of several more FADs in the vicinity, and as our ability to see was reduced as we sailed into the setting sun, we took a cautious approach. Fortunately, no more FADs were spotted and the night remained calm and uneventful.

The next few days gave us a variety of light wind sailing conditions. We tried umpteen sailing configurations with different sails up, down, half way up, halfway down, and everything in between. We poled out the jib, hoisted the spinnaker, and kept ourselves busy trying to keep the boat moving.

The sailing was calm and undramatic, and life passed easily despite our being healed over a good deal of time with all the issues that entails. The only drama I recall is we had yet another headache with our spinnaker. On this occasion we tried to pull down the sock, a fabric tube that is pulled down over the sail to douse it, only to find that the sock wouldn’t budge. Somehow a line had wrapped around it and was cinching the sock tight as we tried to pull it down. Ultimately, we simply lowered the spinnaker by dropping the halyard, and though a small amount fell in the sea we simply tied it to the dinghy to dry. Though we need more practice, the asymmetrical spinnaker has been a great boon to the sail wardrobe, and gets less challenging (scary) as we gain experience with it.

Later the wind built slightly and settled on 15 knots on the beam. The sea was remarkably calm and flat and Taurus sped along at 7-8 knots for hour after hour, day after day. We’ve never had sailing so fast and easy. Of course, it couldn’t last forever, and just when we started to talk about getting into Australia a day early the wind died away. The motor came on and we slowly chugged across a sea whose flatness would have done credit to any billiard table. The temperature remained around the 30 degree mark and the sea was such a beautiful azure that we were soon tempted to throw over a safety line and jump in.

After some 24 hours the wind started to pipe up again and we were soon able to turn the engine off and set the sails. That night when I was off watch, Cara came and woke me up and told me that there was a big storm approaching. She had been watching the squall on radar and changed course to try and avoid it, but it was too big and moving too quickly for us to get around.

We quickly lowered the sails as the wind can increase dramatically in squalls, and prepared the boat to the best of our ability — disconnecting all electrical appliances that we could disconnect, checking everything was tied down tight, girding our loins, and so on. As the storm got closer the lightning was almost constant, and the gap between the flash of lightning and the roar of the thunder became ominously short before non-existent. As we were unable to outrun the storm our best option seemed to be to turn around and aim for the thinnest part and try to break through in the shortest time possible. The following pictures give an idea of the visual experience:

Pretty soon we were engulfed. The storm, as it appeared on radar, constantly changed in shape and intensity around us. Perhaps foolishly I tried to steer for the green areas and thinnest sections, though always with a NE heading in mind. In hindsight I would have been better off just steering in a straight line. Counter to our expectations, the wind died and instead the heavens opened and we were met by a monsoon-like downpour. Of course, the big worry in these situations is that the boat will be struck by lightning. I had actually been talking to someone in Noumea who had had this experience just before leaving; his rigging, sails, electronics, and anchor chain were all wrecked by the strike. Luckily, he was fully insured, but for us, having only third party insurance, such devastation would be… well devastating, or at least very expensive to put right, so we were on tenterhooks to get through to the other side as soon as possible. It took what seemed like a long time, I would have sworn the storm stopped on top of us, but within half an hour or 45 minutes we were through the other side and relishing the tranquil darkness of the skies ahead. How you can sail a steel boat with a 13.5m aluminium mast through an electrical storm of this magnitude and not be struck I don’t know. In the UK, cricket teams and such like are warned not to take shelter under lone trees if it starts to rain because several people have been killed when isolated trees have been hit by lightning. There can be no more isolated tall object than a yacht at sea, and there was no shortage of lightning, so we can only be grateful that we emerged unscathed.

After the excitement we settled down to sailing again. Our course hadn’t taken us far enough north so we couldn’t get around Breaksea Spit, a sandy bar that guards the approach to Bundaberg. We therefore had to tack and beat into a freshening wind for about four hours before we could tack back and begin the long, last haul to the west. Said quickly it would seem that this would take no time, but in fact it took another full day of sailing.

As light fell the wind increased and we were soon hurtling along at 8 knots again, but this time the sea state provided a short, sharp chop that kept Taurus rolling from one side to the other. The uncomfortable sail only made us want to get into harbour as soon as possible, but as the anchorage for Customs lies up a river we felt it prudent to wait until daylight to make our entrance.

Once more we assumed our standard watch schedule: three hours on, three hours off. At about midnight I noticed a number of bright white lights ahead of us. According to AIS there were no boats or ships in front of us, the radar showed nothing, and the chart made no sense of what I was seeing. As we were speeding towards these strange objects, about a dozen of them spread across the horizon in front of of us, I woke Cara to see if younger eyes and keener intellect could make sense of the situation.

We were both non-plussed, but eventually it became clear that the lights were fishing boats. The brightness of the white lights totally obscured their nav lights, their AIS were all turned off (as is common for fishing boats for reasons of commercial competitiveness), but their failure to appear on radar remains a bit of a mystery — possibly a consequence of the chop and radar filter settings. Due to the brightness of the lights against a backdrop of pure darkness it was difficult to tell how far away the fishing boats were. We were still being steered by the Hydrovane, which in the wind and confused sea was tending to allow Taurus to wander a little. Despite our having settled on a course that would take us between two boats we still managed to point straight towards one of the fishing boats at one point, which then called us up on VHF to tell us that we should change course and that they were trawling at a couple of knots. Cara, tired and not impressed by the deliberate obscurity of these commercial vessels, suggested that the skipper put on his AIS so we could see where he was and where he was heading, but this good advice was studiously ignored. Still unsure as to how far away the fishing boats were and which direction they were heading in, we began hand steering and finally navigated this shifting hazard, though not before it seemed like another fishing boat wanted to play chicken with us, and steered straight towards us. No doubt these fishermen have their own imperatives, but after seven days at sea, sleeping a maximum of three hours at a time, being forced to face a confusing and unnecessarily hazardous situation because people have chosen to turn off their vessels safety devices was a bit frustrating.

After the fishing boats we were free to try and get some more sleep. Our planned arrival time, day break at 5:30 am, meant that we could aim for another hour and a half each. As the sun rose we headed up the channel towards the river entrance and enjoyed one last sunrise at sea.

The dreaded Australian Customs and Bio-Hazard people turned out to be helpful and friendly, though they still charged us A$550, and before we knew it we had been admitted into Australia. Somehow, unable to sleep despite being dog tired, we enjoyed a busy day, finding our way around the marina and socialising with friends old and new.

We had a lot to prepare for in the next week or so. Cara is returning to NZ to do some work, whilst I fix a few things on the boat. Hopefully everything goes smoothly…

Leave a comment