Tuesday May 7th saw up early as we had an appointment with NZ Customs at 8:30 am. The guys were friendly and relaxed but they made a point of making sure we understood that when we left we had ‘cleared customs’ and had to go straight back to Taurus and leave. No stopping for coffee, no visiting friends, no last minute errands.

It was a beautiful, sunny day and as we motored out of the marina a girl on large steel ketch called Saltlines yelled across, “Where are you heading?” With equal measure of trepidation and pride I yelled back “Tonga!” There was very little wind so once we were at sea we set out to hoist our spinnaker. This is a sail that we have never used with just the two of us on board because it’s a massive piece of cloth, designed for light air, and if the wind builds a spinnaker can get out of control very quickly. If you want to see what I mean just google something like ‘spinnaker fails.’

With the spinnaker up we began making decent speed, but the wind slowly built and soon enough we had to take the sail and pole down again. That day we went from main and spinnaker, to main and jib, and slowly reefed the sails down until we hoisted the storm jib in about 35 knots of wind. We were sailing conservatively as there had been a number of squalls, including a spectacular thunder and lightning show with driving rain. However, the lack of drive meant the boat wallowed terribly and we watched on the AIS as Saltlines, also heading to Tonga, caught us and then sped away.

The next day the wind blew from astern and we finally poled out the jib to stop it slatting as the boat rolled and the gusts rose and fell. We ended up travelling at quite a good rate of knots, which helped with the sloppy seas so much that I was loathe to take it down even as the wind gained in strength. On an extended passage a crew of just two people can’t really afford to sail too conservatively. Faffing around with the sails all night means you don’t get enough rest, the slower you go the harder life on board becomes due to the motion of the boat, and, of course, the slower you go the longer you have to spend at sea, with the inherent danger of being caught in bad weather. So, with all that in mind we left the jib poled out and fairly rocketed along all night.

Our first two days at sea were pretty rough due to the sea state. We knew that this would be the case, but the later weather pattern suggested light winds and our heavy steel boat doesn’t sail well in light air, so we chose rough seas and wind over motoring. As it happened many of the boats that waited in Opua were to experience rough weather near Minerva when we were tucked up inside in the shelter of the reef.

So what is it like to spend thirteen days crossing a small part of the Pacific? Obviously, Cara and I are pretty new at the game, and there are many books written by sailing legends that can provide a much better, more accurate, and more nuanced narrative. My short answer would be something unhelpfully ambiguous like, ‘it is miserable and glorious.’ The miserable aspect is easy to quantify. The eminently quotable Dr. Samuel Johnson, of English Dictionary fame, once claimed that “no man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; for being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned… a man in a jail has more room, better food, and commonly better company.” In a similar vein, J. Boyd Shellback argued that “he that would go to sea for pleasure, would go to hell for a pastime.” Though these gentlemen are referring to sailing in the days of yore, the sea hasn’t changed a great deal, and the theme retains a good nugget of truth.

In this modern world we generally live incredibly comfortable and secure lives. When we have to face the rare prospect of being uncomfortable the experience is finite, a few minutes, a few hours perhaps. When you go to sail across an ocean in a small boat being uncomfortable lasts day after day after day, and how very uncomfortable it is. Imagine living in a small room, perhaps half the size of your living room, in which you have kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, and living room. You can’t leave this room. Now add an extra person, so that you have to negotiate the space with them and work around them. Put that room at 30 degrees, so that whenever you put something down it immediately tries to slides away and crash to the floor; a not quite shut door swings and slams shut, generally with your fingers in the jam; you have to think about which side of the room to sit on — get it wrong and you’ll be thrown out of your seat; the drain of either your kitchen or toilet sink will be below sea level, so that should you open the sea cock to drain the sink you will find that rather than the sink emptying, the sea will pour inside. The sea will continue filling your room until you notice and reclose the seacock — best not to leave it open too long as there is a lot of sea and not a lot of volume in a boat (we once took on about 200 litres of seawater in this fashion). If you can’t open the seacock how do you get rid of the dirty water from the dishes that’s sloshing round and trying to escape the sink? Silly things like this are frustrating for a day or two, but after thirteen days they become a real PITA. Now imagine this oddly angled but stationary room swinging between 30 degrees to the left and 30 degrees to the right, your living space undulating irregularly like a madly erratic pendulum. Add some violent vertical movements, up and down, the odd horizontal slam sideways as a wave smashes against the hull. Imagine trying to making dinner, going to the toilet, trying to sleep. Remember that you and your partner have to maintain a constant watch for other vessels, this demands a watch system through the hours of darkness that will allow you, on a good night, perhaps 3-5 hours of broken sleep. This ‘room’ doesn’t sail itself. Adjusting the sails, the course, the helm, is a constant demand, a demand that you can’t ignore if you’re sleepy or a bit fed up, because if you get it wrong you can break your boat, yourself, or your crew-mate, and help is a long, long way away. Should you happen to fall overboard, perhaps whilst reefing your main at 3am in a gale and driving rain, then you are simply dead. There have been numerous incidents of professional sailing teams, five or six strong, being unable to rescue lost crew members (even when they are still attached to the boat). For a short handed, two person, crew, the chances of a successful rescue are miniscule. For this reason, sailor’s lore often compares the sea to molten lava — fall in and you’re history. All of this sailing business depends upon an immediate relationship with the weather. If its raining you get wet; if its hot you sweat, you can’t just open the windows because the sea will come crashing in. Of course we use weather forecasts and prediction services, but often they are wrong. This results in sometimes having to motor. When we left Minerva a wind was supposed to help us half way, but it didn’t appear. When a wind did spring up it was on our nose and the size of the swell prevented us being able to get anywhere near Tonga. On one tack we sailed North West, on the other South East — but Tonga was East and the only way we could get there was by dropping the sails and motoring, for two days. Two days of the engine droning away as it consumed expensive, smelly diesel. Naturally, it would be nice to be able to throw your dummy out of the cot and quit at times, but once you’re on the roller coaster there ain’t no getting off. You are trapped in your noisy, smelly, deranged room that won’t remain still for two seconds, in the company of a tired, grumpy, seasick partner, that hates you for convincing him/her that this was a good idea. Does days of this sound fun?

So, where, you may wonder, is the up side in all this? Sailing boats, in my humble opinion, are the least inanimate of inanimate objects. You will never be able to persuade a sailor that his boat doesn’t have a soul, because if they didn’t feel their boat’s soul they wouldn’t sail. In between the misery, fear, and nausea there are joyous days when the wind, sea, and course combine to make the boat a living creature that transports its crew to magical destinations as if it were a flying carpet. It has been said, with some justification, that sailing is the most expensive way in the world to travel for free — but sailing is more than travelling, its a way of communing with nature, of breaking the shackles of life in the 21st century, of experiencing the immediacy of life and finding reward in the experience. Sailing is not like driving, not like catching a train, no where near the oh so sanitised experience of flying. Sailing, on a good day, is pure, elemental, exhilaration. This sense of freedom more than makes up for the bad days, obviously, because otherwise no-one would sail.

On our sixth day at sea Cara and I arrived at South Minerva Reef. The two Minerva Reefs (North and South) belong on any sailor’s bucket list. They are surreal. To start, you can’t actually see them as you approach, and it is only when you are frighteningly close that you see a rim of white water as the sea crashes against the coral.

The southern reef is in the shape of a figure ‘8’ with entry into one of the circles through a gap in the coral. You approach the reef unable to see it, essentially following your chart inside, and suddenly you find yourself in twenty metres of sheltered water and able to drop anchor. All around all you can see is ocean, often rough waves, but you are calm and still. After days of constant movement the sensation of peace is magnified to a near religious experience. The Minerva Reefs are special places.

The following day we sailed for four hours to North Minerva, and experienced the same bizarre sense of finding haven where there really shouldn’t be any. The first day we swam in the beautifully clear water. Anchored in 16 metres we could easily see the seafloor. Next day Cara noticed a school of fish beneath the boat. We grabbed our fishing rods to try and catch dinner but the fish weren’t biting and we soon realised why. Large tuna type fish were diving through the school that were obviously seeking protection from our hull. I ran downstairs to get the spear gun intending to jump in, but as I got to the dive platform I saw several of these tuna swimming towards me. In the second or so I had before they disappeared I calculated trajectory, velocity, depth and surface refraction, pulled the trigger, and to my eternal surprise missed my toes and speared a fish!

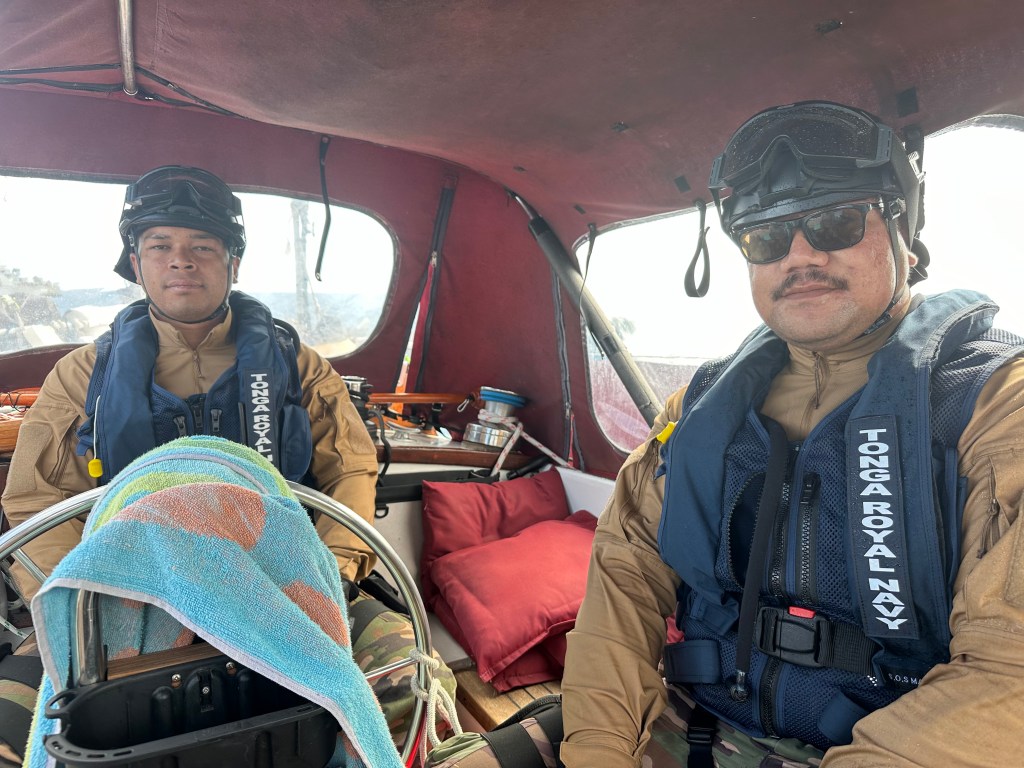

That afternoon the Tongan Navy came to tea — at least we offered them tea when they came to see what we were up to. The guys were built like the proverbial outdoor facilities, so big they could hardly fold themselves inside the dodger, and armed to the teeth with half a rugby team in an IRB for backup and a naval ship sitting behind us; we made sure we were super polite.

We sheltered at Minerva for a couple of days as a gale blew through and decided to make a run for Tonga, about three hundred nautical miles away, two and a half day’s sailing. Before we left we went snorkelling in the incredible water and went for a walk on the reef.

The sea life was pretty incredible, and we did see a massive crayfish, which the Minerva’s are renown for, but we still had a fridge full of Amber Jack so we left it in peace.

The weather window to get to Tonga was pretty marginal, with one day’s good sailing predicted following by head winds and then zero wind. Not wanting to motor too much we decided to take advantage of the decent day to get half way and then tack the rest. As I mentioned above this plan didn’t work out and we had to motor most of the way, which was disappointing. Still, other people who left after us had an even more miserable time with stronger headwinds, so we can’t complain.

One exciting incident en-route was finding lots of water in the bilge. It is a tenet of sailing that the sea should stay outside of the boat, so this was of concern. We heaved to, a way of placing your sails in opposition so that the boat essentially stops, and quickly checked the seacocks (the holes in the hull that can let water in) to work out where the water was coming from. Regular readers of the blog will remember that we had a big oil leak in Whangarei. When sorting out that mess we had to move a plastic box from beneath the engine that the anchor compartment drained into. We felt that not a lot of water would drain from said compartment (sealed except for a small hole that allows the 10mm chain in and out) so replaced it with a smaller container that we placed under the cabin soul (floor). This container had filled and then overflowed and was under such pressure that we had a small fountain when we removed the hose. The anchor compartment was sealed with silicone for our passage but I had left the bung out whilst at Minerva. During the gale we had torrential rain but I didn’t imagine that that much water could have found its way in. This seems to be the way of boats — you try to fix something which causes a chain reaction which ends in something biting you in the bum. Needless to say we have kept a close eye on the container since, and might return to the old system. Whilst stopped we also checked the engine oil (which was fine!), and filled up the diesel tank.

After two days of trying to sail but being unable to get any closer to our destination we bit the bullet and motored, finally ‘arriving’ at Tonga at about 1 am on Sunday 19th of May. Not wanting to enter the reef strewn area in the dark we hoved to again and gently jogged along at about 1 knot until 5:30 am when it gets light. We then sailed into Tongatapu Harbour to clear customs at the city of Nuku’alofa. This again is an odd experience as the chart warns of all manner of ‘land,’ which is in fact underwater reef, so you follow a torturous route in, trusting entirely to the chart plotter. The customs mooring is famously rough concrete, so we were delighted to be asked to moor alongside a larger yacht that had just beaten us in. ‘Yes Sir!’ we said. The customs formalities went smoothly, though the quarantine officer ripped us, and several other yachties, off —the $23 fee being elevated to $50. Have a beer on us mate, what goes around comes around.

Since our arrival we have been catching up on sleep, and spending a lot of time swimming because it is very hot and humid. Any activity results in sweat beading on the end of your nose and dripping into your lap. Yesterday we took the dinghy to town and wandered round Nuku’alofa. I wasn’t sure what to expect but I was surprised by how few people speak English, and how much damage remains from the tsunami a few years ago. There are few facilities here but we intend to stay till Saturday as there is a rally party at ‘Big Mamma’s,’ and who could miss that?

Leave a comment